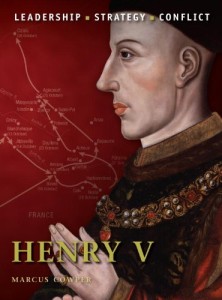

Marcus Cowper

Henry V

(Osprey, 2010) 64pp. $14.95

Marcus Cowper’s Henry V is the eighth book in Osprey Publishing’s “Command” series, each of which summarizes the life of a military commander from history. Like with most of Osprey Publishing books, Henry V is not intended to be an advanced scholarly work, but serving as a introduction to the history of a given period or personage. Some readers, however, might already be familiar with other Osprey publications featuring Henry V, such as Matthew Bennett’s Agincourt 1415: Triumph Against the Odds, or Christopher Rothero’s The Armies of Agincourt.

So what’s different? These other publications focus only on Henry V’s role in the Agincourt campaign, or his later campaigns against the French. Cowper’s work is more biographical. While Henry’s military career remains prominent throughout, Cowper compares the “mythic” Henry V, the ideal Christian king read about in works such as Shakespeare, with the “real” Henry. Cowper argues that the image of Henry has been conflated by literature, and does not represent the historical reality.

There is no doubt that Henry V was a Christian leader. Yet, as Cowper asserts, Shakespeare and even movies from the twentieth century have fictionalized Henry, giving audiences a distorted historical view. Even historians such K. B. Macfarlane, who declared Henry V to be the greatest man to rule England, have fallen into the trap of believing in the myth. These works often neglect Henry’s other attributes, Cowper argues, such as his logistical abilities to maintain and standing army all year, or his aptitude for reigning with impartial law and order as king. Certainly Henry was religious; he supported the Carthusian Order. But he was ruthless. He put down Lollard heresies, hung men who disobeyed him, and ordered the execution of prisoners at Agincourt.

To analyze these different facets of Henry, Cowper covers his whole life, beginning in his early years when he was known as Henry of Monmouth. Yet by the age of thirteen, Henry had experienced political turmoil, had been trained as both a warrior and intellectual, and after his father usurped the throne he suddenly become the next in line to inherit the throne. Soon after he participated in campaigns against the Welsh. By the time he became king in 1413, Henry V has the practice and experience to become a great military leader. His triumphs at Agincourt and later campaigns were not flukes, but years in the making.

Logistics was key to these victories, Cowper asserts, especially in the conquests of Normandy and France in 1417-20, and 1421-22, respectively. Indeed, these were high points for the English in the Hundred Years’ War. Henry V’s forces were typically better organized that their French opponents, able to maintain forces in the field with ample supplies of arrows. Cowper adequately shows how indentureship and contracts worked in raising men-a-arms and bowmen, but was this part of Henry V’s own genius, or just part of how England was just transitioning way from the feudal host? Cowper does not discern. He also overlooks how Henry kept his men supplied in the field. He does, however, summarize these campaigns well.

The centerpiece of the book is the Agincourt campaign. At Agincourt itself Henry V displayed his ruthlessness by executing conspirators before the campaign and captured prisoners at during the Battle of Agincourt. Were these executions really from ruthlessness or by necessity? Cowper points out that Henry’s forces could not manage such a large amount of men-at-arms since they were being hard pressed by the French. He cites primary sources at lets the reader judge for him or herself. One thing is clear, as Cowper points out, is that the victory at Agincourt lended to the creation of the “mythic” Henry V in Shakespeare.

“Opposing Commanders,” one of the more interesting sections of the book, compares Henry V with leaders who opposed him, such as Owen Glendower who led the Welsh Revolt beginning in 1400. We also discover about how Henry dealt with the English Magnates against him. Cowper also covers the French lords who campaigned against him. While these sections present a concise history in their own right, each does not explain how Henry defeated the opposition, beyond just being better organized. All of Henry’s adversaries seemed disorganized, feuding. Henry took advantage of this factionalism.

Readers should not expect Cowper’s Henry V to be an exceptional scholarly work. It is, however, a good distillation of the information taken from the sources in the book’s short bibliography. He does articulate and support his argument differentiated between the “mythic” and the historical Henry V. Yet given the book’s length, further in-depth analysis is not possible. Many readers already familiar with these works probably won’t find much new with Cowper’s work. New readers will find it as a good starting point for further research.

Stelios V. Perdios