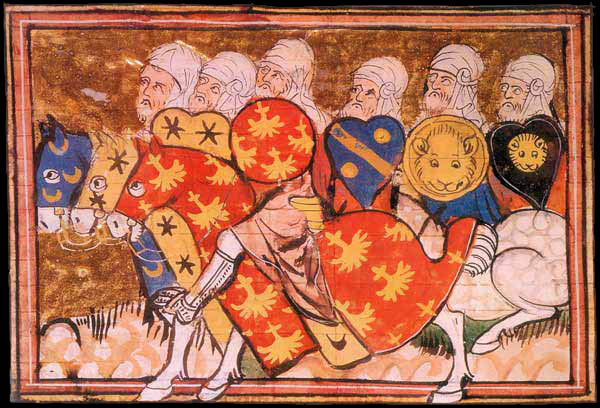

On July 4, 1187, the Crusader army of the Kingdom of Jerusalem suffered a crushing defeat in the hills a few miles to the west of the Sea of Galilee. The victor was that most famous of all medieval Muslim rulers, Salah al-Din Yusuf, better known in the English-speaking world as Saladin. The king of Jerusalem and many of his barons were taken captive on a hill called the Horns of Hattin, and it is from that hill that the battle is named.

Here are four primary source accounts of the Battle of Hattin. The first account of this battle given here is from The Old French Continuation of William of Tyre (Lyon Eracles version), which was written in the early thirteenth-century.

Chapter 40) Now I shall tell you about King Guy and his host. They left the Springs of Saffuriya to go to the relief of Tiberias. As soon as they had left the water behind, Saladin came before them and ordered his skirmishers to harass them from morning to midday. The heat was so great that they could not go on so as to reach water. The king and all his men were too spread out and did not know what to do. They could not turn back for the losses would have been too great. He sent to the count of Tripoli, who led the vanguard, to ask his advice. The message came back that he should pitch his tent and make camp. The king gladly accepted this bad advice, though when he gave him good advice he would never take it. Some people in the host said that if the Christians had pressed on to meet the Saracens, Saladin would have been defeated.

Chapter 41) As soon as they had made camp, Saladin ordered his men to collect brushwood, dry grass, stubble and anything else that could be used to light fires, and to make palisades all round the Christian host. This command was carried out in full. Early next morning he ordered the fires to be lit. This was quickly done. The fires burned vigorously and made an enormous amount of smoke, and this, in addition to the heat of the sun, caused the Christians considerable discomfort and harm. Saladin had commanded caravans of camels loaded with water from the Sea of Tiberias to be brought up and had the water jars positioned near the camp. They were then emptied in the sight of the Christians with the result that they and their horses suffered even greater anguish through thirst.

A strange thing had happened in the Christian host the day they had been encamped at the Springs of Saffuriya, for the horses refused to drink the water either at night or in the morning, and because of their thirst they were to fail their masters when they most needed them.

Then a knight named Geoffrey of Franclieu went to the king and said, ‘Sire, now is the time for you to make the polains with their beards dear to the men of your country. One of the causes of the hatred between King Guy and his Poitevins and the people of this land was that when he became king the Poitevins sang a song in Jerusalem which greatly incensed the men of the kingdom. The song went:

Maugre li Polein,

Avrons nous roi Poitevin.

This hatred and scorn gave rise to the loss of the kingdom of Jenisalem.

Chapter 42) When the fires were lit and the smoke was great, the Saracens surrounded the host and shot their darts through the smoke, thus wounding and killing men and horses. When the king saw the torments that were afflicting his army, he called the master of the Temple and Prince Reynald and asked their advice. They counselled him to join battle with the Saracens. He ordered his brother Aimery, who was the constable, to organize the divisions. He did as best he could. The count of Tripoli, who had led the vanguard at their arrival, led the first division and was out in front. In his division he had Raymond, the son of the prince of Antioch, with all his company and the four sons of the lady of Tiberias, Hugh, William, Ralph and Oste. Balian of Ibelin and Count Joscelin made up the rearguard. Just as the divisions were being drawn up and the battle lines made ready, five knights from the count of Tripoli’s division deserted and went to Saladin and said, ‘Sir, what are you waiting for? Go and take the Christians for they are all defeated.’ When he heard these words he ordered his men to advance, and they started off and drew near to the Christians.

When the king saw that Saladin was coming against him, he ordered the count of Tripoli to charge. It is a right belonging to the barons of the kingdom that, when the whole army is in their lordship, the baron on whose land the battle is to take place leads the first division and is out in front: on entering his land he leads the vanguard and on leaving leads the rearguard. Accordingly, since Tiberias was his, the count of Tripoli took the forward position. The count and his division charged at a large squadron of Saracens. The Saracens parted and opened a way through and let them pass. Then, when they were in their midst, they closed in on them. Only ten or twelve knights from the count’s division escaped. Among them were the count of Tripoli himself and Raymond, the son of the prince of Antioch, and the four sons of the lady of Tiberias. When the count saw that they were defeated, he did not dare go to Tiberias which was only two miles away, for he feared that if he shut himself up in there and Saladin found out, he would come and take him. He went off with such company as he had and came to the city of Tyre.

After this division had been defeated the anger of God was so great against the Christian host because of their sins that Saladin vanquished them quickly: between the hours of terce and nones [7 am to 3 pm] he won the entire field. He captured the king, the master of the Temple, Prince Reynald, the marquis William, Aimery the constable, Humphrey of Toron, Hugh of Jubail, Plivain lord of Botron, and so many other barons and knights that it would take too long to give the names of all of them. The Holy Cross also was lost.

Later, in the time of Count Henry [of Champagne, who ruled the remaining portion of the kingdom of Jerusalem in 1192-97], a brother of the Temple came to him and said that he had been at the great defeat and had buried the Holy Cross and knew where it was; if he could have an escort he would go and look for it. Count Henry gave him an escort and his permission to go. They went secretly and dug for three nights but could not find anything. Then he went back to the city of Acre.

This disaster befell Christendom at a place called the Horns of Hattin, four miles from Tiberias on Saturday 4 July 1187, the feast of Saint Martin Calidus. Pope Urban III was governing the Apostolic See of the Church of Rome, Frederick was emperor in Germany, Philip son of Louis was king of France, Henry au Cort Mantiau was king of England, and Isaac was emperor in Constantinople. 79 The news of it struck the hearts of those faithful to Jesus Christ. Pope Urban who was at Ferrara died of grief when he heard the news. After him was Gregory VIII, a man of saintly life, who held the papal see for two months before he too died and went to God. After Gregory came Clement III to whom Archbishop Joscius of Tyre brought a truthful account of the news as you will find written below.

Chapter 43) Saladin had left the field rejoicing at his great victory and was in his camp. There he ordered all the Christian prisoners who had been taken that day to be brought before him. First they brought the king, the master of the Temple, Prince Reynald, William the marquis, Humphrey of Toron, Aimery the constable, Hugh of Jubail and several other knights. When he saw them all lined up in front of him, he told the king that he would have great satisfaction and would be held in great honour now that he had in his power prisoners as valuable as the king of Jerusalem, the master of the Temple and the other barons.

Then he ordered that syrup diluted with water be brought in a gold cup. He tasted it and gave it to the king to drink and said, ‘Drink deeply.’ The king, who was extremely thirsty, drank and handed the cup to Prince Reynald. Prince Reynald would not drink. When Saladin saw that he had handed the cup to Prince Reynald he was angered and said to him, ‘Drink, for you will never drink again.’ The prince answered that if it pleased God he would never drink or eat anything of his. Saladin asked, ‘Prince Reynald, by your law, if you held me in your prison as I now hold you in mine, what would you do to me?’ He replied, ‘So help me God, I would cut off your head.’ Saladin was greatly enraged at this most insolent reply and said, ‘Pig, you are my prisoner and yet you answer me so arrogantly.’ He took a sword in his hand and thrust it right through his body. The Mamluks who were standing nearby rushed at him and cut off his head. Saladin took some of his blood and sprinkled it on his own head in recognition that he had taken vengeance. Then he ordered that Reynald’s head be brought to Damascus, and there it was dragged along the ground to show the Saracens whom the prince had wronged that vengeance had been exacted.

The second account of the battle comes from a different version of this text – Colbert-Fontainebleau Eracles

Now I shall tell you about King Guy and his host. They left the Springs of Saffuriya to go the relief of Tiberias. As soon as they had left the water behind, Saladin came before them and ordered his skirmishers to harass them. From morning until mid-day they rode at great cost up towards the valley called Le Barof, for the Turks kept engaging them and so impeded their progress. The heat was very great and that was a source of great affliction, and in that valley there was nowhere they could find water. By midday they had only got half way between the Springs of Saffuriya and Tiberias. The king asked advice as to what to do. The count of Tripoli gave him evil counsel and advised him to leave the road he was on since it was too late for him to get as far as Tiberias in view of the great attack that the Turks were making; they could not camp where they were because there was no water, but nearby, beyond the mountain to the left, there was a village named Habatin (Hattin) where there were springs of water in great plenty, and there they could camp for the night; in the morning they could go on to Tiberias in great strength. The king agreed to this advice, but it was bad. Had the Christians kept to their original plan, the Turks would have been defeated. But he accepted the count’s proposal and left the road he was going and turned off to the side. In the process the Christians, out of their desire to get to water, put themselves at a disadvantage, and as a result the Turks took heart and attacked them from all sides. Also they moved on and got to the water first. So it came about that our people stopped on the summit of the mountain at the place called the Horns of Hattin. Then King Guy called on the count to advise the Christians and himself. The count replied that if the king had accepted his original advice, it would have been much to his great advantage and to the salvation of Christendom. But now it was too late: ‘There is nothing for it,’ he said, ‘I cannot now offer any advice other than to try to make camp and to pitch your tent on the top of this hill.’ So the king accepted his advice and did what the count had said. On the summit of this mountain where King Guy was captured, Saladin had made a mosque which still stands in celebration and remembrance of his victory.

When the Saracens saw that the Christians were making camp they were delighted. They camped around the Christian host so close that they could talk to one another, and if a cat had fled from the Christian host it could not have escaped without the Saracens taking it. That night the Christians were in great discomfort. Great harm befell the host since there was not a man or a horse that had anything to drink that night. The day that they left their camp was a Friday, and the following day, the Saturday, was the feast of Saint Martin Calidus, towards August. All that night the Christians were stood to arms and suffered much through thirst. The following day they were all got ready for combat, and for their part the Saracens did the same. But the Saracens held off and did not want to engage in fighting until the heat got up. Let me tell you what they did. There was a big swathe of grass in the plain of Barof, and the wind got up strongly from that direction; the Saracens came and set fire to it all around so that the fire would cause as much harm as the sun, and they stayed back until it was high terce [towards noon]. Then five knights left the squadron of the count of Tripoli and went to Saladin and said, ‘Sire, what are you waiting for? Attack them. They can do nothing for themselves. They are all dead men.’ Then too some foot sergeants surrendered to the Saracens with their necks bared, such was their suffering through thirst. When the king saw the affliction and anguish of our people and the sergeants surrendering to the Saracens, he ordered the count of Tripoli to attack the Saracens for it was on his land that the battle was taking place and so he should have the first charge. The count of Tripoli charged at the Saracens. He thundered down the slope into the valley, and as soon as they saw him and his men advancing towards them the Saracens parted and made a way for them as was their custom. So the count passed through, and the Saracens closed ranks as soon as he had passed and attacked the king who had stayed where he was. Thus did they take him and all who were with him, except only those who were in the rearguard and escaped.

When the count of Tripoli saw that the king and his men were taken, he fled to Tyre. He had only been two miles from Tiberias, but he did not dare go there for he knew well that, if he did, it would be taken and he would not be able to escape. The prince of Antioch’s son, who was called Raymond, and the knights that he had brought with him and the count’s four stepsons escaped with him. Balian of Ibelin who was in the rearguard also escaped and fled to Tyre, as did Reynald of Sidon who was one of the barons.

[smartads]

The third version comes from a Letter to Archumbald, the Hospitaller master in Italy. This letter seems to have been written less than two months after the battle.

We shall tell you, Lord Archumbald, master of the Hospitallers of Italy, and the brothers about everything that has taken place in the lands beyond the seas.

You must know that the king of Jerusalem was at Saffuriya around the feast of the Apostles Peter and Paul (29 June) with a huge army of at least 30,000 men. He had been properly reconciled with the count of Tripoli, and the count was with him in the army. And behold, Saladin, the pagan king, came against Tiberias with 80,000 cavalry and captured it. The king of Jerusalem was informed, and he moved from Saffuriya and went with his men against Saladin. Saladin attacked them at Meskenah on the Friday after the feast of the Apostles Peter and Paul (3 July). Battle was joined, and for the whole day they fought bitterly. But night put an end to the strife. With the coming of night, the king of Jerusalem pitched his tents near Lubiyah, and next day – the Saturday – he set off with his army. At around the third hour the master of the Temple charged with all his brothers. They received no assistance, and God allowed most of them to be lost. After that the king with his army forced his way with great difficulty to a point about a league from Nimrin, and there the count of Tripoli came to him and had him pitch his tents near a mountain that is like a castle. They could only get three tents up. Once the Turks saw them marking out their defences, they lit fires round the king’s army, and so great was the heat that the roasting horses could neither eat nor drink. At this point Baldwin of Fatinor, Bachaberboeus of Tiberias and Leisius, with three other companions, separated themselves from the army and went to Saladin and, sad to say, renounced their faith. They surrendered themselves and told him the situation in the king of Jerusalem’s army and its dire condition. Thereupon Saladin sent Taqi al-Din against us with 20,000 chosen knights. They charged at the Christian army, and from nones until vespers the fighting was most bitter. As a consequence of our sins many of our men were killed, and the Christians were defeated. The king was captured and the Holy Cross. So too were Count Gabula, Miles of Colaverdo, Humphrey the Younger [of Toron], Prince Reynald who was captured and killed, Walter of Arsur, Hugh of Jubail, the lord of Botron and the lord of Maraclea. A thousand more of the better men were captured and killed, with the result that no more than 200 of the knights or footsoldiers escaped. The count of Tripoli, the lord Balian and Reynald lord of Sidon got away.

The fourth version gives an account of the Battle of Hattin from a Muslim point-of-view. Masalik al-absar fi mamalik was written by Sihab al-Din b. Fadl Allah al-‘Umari in the fourteenth century. It is an encyclopedia, made of twenty-seven volumes, the last of which is a history of the Arabs from 1146 to 1343. His history is often based on the works of earlier writers, and he is a valuable source for the Muslim viewpoint in their conflict with Crusaders.

In the year eighty-three [583 AH / 1187 AD] Saladin’s campaign and conquests began. This year the sultan gathered the army and set out with a division of soldiers to lay siege to Kerak, because he feared that the lord of Kerak should attack pilgrims. He sent another division with his son Malik al-Afdal to raid the region of Acre, and they took a lot of things as booty. The sultan then went to Tiberias, took up his quarters there, laid siege to the town and occupied it by force of arms. But the citadel resisted. Tiberias belonged to the count, lord of Tripoli, who had exchanged gifts with the sultan and had accepted obedience to him. The Franks sent priests and the patriarch to the count to keep him from his agreement with the sultan. They rebuked him, and he was brought along with them.

The Franks gathered to meet the sultan, and the battle of Hattin took place. With this very important battle Allah gave dominion over the coast and the holy city [Jerusalem].

When the sultan occupied Tiberias the Franks brought together their cavalry and their infantry, and they marched against the sultan who rode from Tiberias to meet them on the Sabbath-day, five days from the end of Rabia II. The two armies met and the fighting between them was very hard.

When the count saw how serious the situation was, he attacked the Muslims who were in front of him. There was Taqi al-Din ‘Umar, lord of Hama, and he opened his ranks to the count and let him pass, but then he closed up behind from the battlefield and arrived at Tripoli. He lived there for some time and died of this deceit.

And Allah helped the Muslims to be victorious, they surrounded the Franks on all sides and destroyed them, killing and capturing them. The group of prisoners included the great king of the Franks, the prince Reynald, lord of Kerak, the lord of Jubail, Humphrey, the son of the Humphrey, the grand master of the Temple and a lot of Hospitallers. From that time the Franks never managed to invade Syria.

When the battle had come to an end the sultan sat down in a tent. The king of the Franks was brought in, and the sultan asked him to sit down at his side. The king was very hot and thirsty, and the sultan gave him snow-covered water to drink, and the king of the Franks gave some of it to the prince Reynald, lord of Kerak. But the sultan said to him; “This damned man did not drink water with my permission, if it had been so he would be safe.”

The sultan then spoke to the prince and rebuked and scolded him for his breach of faith and his attempted attack against the two sacred famous cities. The sultan himself rose and with his own hand he cut the prince’s neck. A violent fear seized the king of the Franks, but the sultan reassured him.

The first three accounts are found in The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, edited and translated by Peter W. Edbury (Ashgate, 1998). We thank Ashgate Publishing and Peter W. Edbury for their permission to republish these items. The fourth text was first published in Saladin and the Crusaders: Selected annals from Masalik al-absar fi mamalik al-amsar, translated by Eva Rodhe Lundquist (Lund: Studia Orientalia Lundensia v.5, 1992). We thank Eva Rodhe Lundquist for her permission to republish this section.