Walter, archdeacon of the diocese of Thérouanne, spent his youth among the regular canons of Saint Martin of Ypres whence he was called by John of Warneton, bishop of Thérouanne in 1115. John made him archdeacon of Flanders in 1116 at a relatively early age, a task which brought him into frequent contact with Count Charles, whose confidence he appears to have enjoyed. He in fact met with Charles shortly before the assassination. John of Warneton asked him to write a history of Charles’s life, the Vita Karoli comitis Flandri, immediately after the assassination, and Walter completed the work between July and September 1127. Walter’s works suggest that he had been well educated, and he was, like his bishop, devoted to the “Gregorian” reform movement. For more on Walter, see M. Duchet, “Sur un point erroné de l’Histoire littéraire de la France par les Bénédictins,” Mémoires lus à la Sorbonne dans les séances extraordinaires du Comité Imperial des travaux historiques et des sociétés savantes . . . histoire, philologie et sciences morales 8 (1867/68), 199-211; N. Huyghebaert, “Gautier de Thérouanne,” Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques 20 (Paris, 1984), 115-16; and The Narrative Sources from the Southern Low Countries, 600-1500, University of Ghent, ID numbers G009 and G010. The edition of the charters of the bishops of Thérouanne that is currently being prepared by Professor Benoît Tock of the University of Strasburg will also help us fill in some pieces of Walter’s biography. On the hagiographical context in which Walter composed his lives of Charles and John, see I. Van ‘t Spijker, Gallia du Nord et de l’Ouest. Les Provinces ecclésiastiques de Tours, Rouen, Reims (950-1130), Hagiographies, ed. G. Philippart, 2 (Turnhout, 1996), 239-47, 263-79. ~ Jeff Rider, Dept. of Romance Languages & Literatures, Wesleyan University

From Walter of Thérouanne, Vita Karoli comitis Flandri

16. The feud between Burchard and Thangmar.

And so the ancient serpent [Apc 12.9] and enemy of humankind, seeing this opportunity to exercise his malice, immediately hurled himself into the midst of these ill-willed, preening men. And since he who boasts that he is king over all the sons of pride had set the throne of his realm in their minds, he cunningly prepared another snare for them in which they might be all the more desperately entangled and brought down. For a certain Burchard, a nephew of the provost, the son of his brother Lambert, a most haughty man and great in his own eyes, began a bitter feud, albeit for a very small cause, with his neighbor Thangmar – who was reputed to be greatly devoted to disbursing alms to the poor and, especially, to monks – and Thangmar’s nephew Walter, and on both sides this feuding caused no little slaughter of men.

17. The conditions of the truce and their infraction.

But that godly man Charles, by virtue of the authority with which God had entrusted him, often demanded that they negotiate a truce and kept urging them, even against their will, to come to a peaceful agreement, vying to be numbered among those to whom the Truth Himself made a promise when he said:Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God [Mt 5.9]. But the provost and his people, who in their own eyes were stronger and more exalted, suspected that his aim was to protect their enemies and, since they were badly tormented within, as they well knew, by envy, they complained that whatever he tried to do for the common good was in fact done to oppress them. And so, spurred on by goading jealousy and exasperated by all-consuming anger and made haughty by puffing pride, they broke the peace treaty and suddenly attacked the surprised Thangmar (who feared no assault because of the truce), and, having burst into the courtyard below, forced him to flee in fear to the upper stronghold, cut down trees in the orchards, and scattered, pulled down, and destroyed everything they discovered in the lower areas.

From Walter of Thérouanne, Uita domni Ioannis Morinensis Episcopi

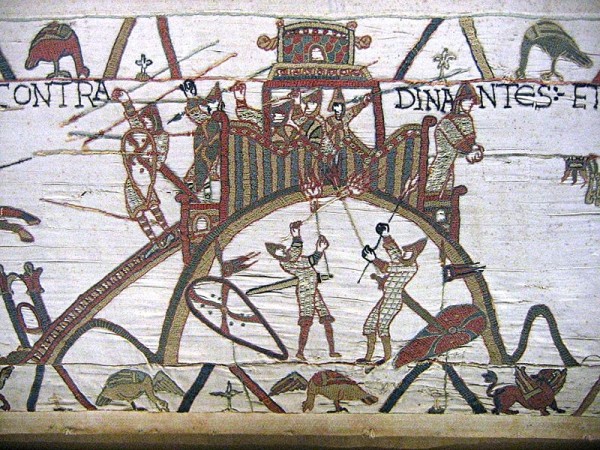

[15.] But it is nonetheless fitting to say something more about his deeds, since we know that many have long wished them to be written down. Many of the brothers wanted them written down even while he was still alive. Fifteen years before he died, when, as always, he was illuminating his diocese with his pastoral care, it happened that he had a dwelling in a village called Merkem where he stayed when he travelled. The building was not like an ecclesiastical hall but might rather be called a castle or fortress, very lofty in keeping with the custom of that region, and had been erected by the lord of the village many years before. The richer and nobler men of that region think of little else than feuding and warring, and in order to be more secure from their enemies and by their greater strength vanquish their equals or oppress their inferiors, it is their custom to build a mound of earth as high as they can, to surround it with a very deep and broad ditch, to fortify the top of the mound on all sides with a solid, wall-like palisade of wooden planks, to place towers all along this wall as best they can, and to build a house or dungeon in the middle of the space within the wall that surveys everything and is disposed in such a way that it can be entered only by means of a bridge that starts at the outer lip of the ditch and is raised little by little and supported by sets of two or even three posts fixed at suitable intervals. Fording the ditch in this way, it rises up until it is level with the top of the mound, where it ends at the very edge of the entrance. It was in this sort of episcopal refuge that he used to stay when he traveled there with his numerous and venerable entourage. When he had confirmed a huge crowd of people both in the church and in the churchyard by the imposition of his hands and anointment with holy chrism, he went back to his dwelling so that he might change his clothes because he had decided to bless a cemetery for the burial of the bodies of the faithful. As he was coming back down from the dwelling in order to do what he had purposed, he stopped for some reason in the middle of the bridge, which was thirty-five feet or more from the ground, with no small throng of people both in front of him and behind him, crowding him in on all sides. Thanks to the scheming envy of our ancient enemy, the bridge suddenly gave way under the weight and fell in ruin to the ground, taking with it both the large crowd of men and their bishop. A huge uproar immediately followed, as cross-beams, planks, and rubble collapsed with great violence and equal noise, and a dark cloud suddenly enveloped the whole scene of destruction to the point that no one could figure out what to do. But God’s mercy quickly intervened, dispersed the darkness, and led his servant unharmed from the danger along with the whole multitude. I am reminded here of the shipwreck of the Apostle Paul, in which God deigned to save the lives of everyone in response to prayer, even though the ships and all their affairs were lost. In this case, even though many men fell and wood was crashing chaotically all over the place, no one was hurt at all, nor did they suffer any material loss. The bishop himself emerged from water up to his knees with a smiling, laughing face, thanking God, and reproached the author of all this malice in these words: “The devil,” he said, “tried to impede God’s work, but he did not prevail, since He is our helper in all things,” and having said this, he proceeded undaunted to the blessing of the cemetery with a lively step.

These texts and translations © Jeff Rider, Dept. of Romance Languages & Literatures, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459, from whom all necessary permissions to reproduce must be sought.