Jared Kirby (ed.)

Italian Rapier Combat: Capo Ferro’s ‘Gran Simalcro’

(Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) 192pp. $65.00

Slowly but surely the works of the great masters of swordplay are being translated into English for the benefit of a much wider readership. We now have Jared Kirby, and the additional aid of Maestros Ramon Martinez and Jeanette Acosta-Martinez in translation, to thank for bringing into that fold Ridolfo Capo Ferro’s Gran Simulacro dell’Arte e dell’Uso della Scherma (“Great Representation of the Art and Use of Fencing”).

Capo Ferro’s seminal 1610 treatise on the use of the rapier provides the reader with a sophisticated vocabulary of techniques. Many of the terms, such as man dritto, imbroccata, and the numerically labeled guardia or wards, are recognizable from other Italian masters, both his predecessors and those following in his footsteps. Kirby includes an extensive glossary of these terms, some of which could prove rather esoteric to a layperson, to allow for greater accessibility. He has also chosen to retain these terms in their original language within the translation.

This book is not intended for the raw beginner. As with so many fight manuals, Capo Ferro presumed foreknowledge of the basics of swordplay from his readers. The same can be said for Kirby’s edition: it takes you straight into the deep-end of Italian fencing. The novice seeking an introductory text on the rapier would be well advised to look elsewhere. However, if this area of study is one with which you are familiar, you should find yourself right at home.

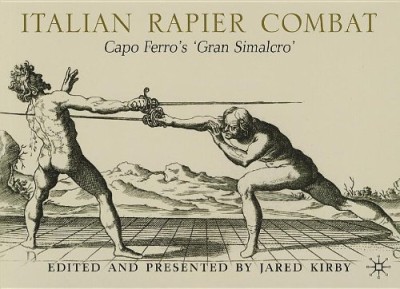

The majority of the illustrations are taken from the 1610 edition. The classical nude figures depicted in exquisite anatomical detail, and the gridded floor upon which they move so as to provide better reference for footwork, are representative of 16th and 17th-century fight manuals. Another edition was published in 1629, in which the backdrop behind the figures was replaced with one depicting scenes from the Bible. Kirby, to showcase the differences in illustration between the two editions, has included several illustrations from this 1629 edition to replace those from the 1610.

The text, rendered into English from what Kirby describes as a linguistically maddening 17th century Italian, begins with Capo Ferro establishing and defining his fencing terminology. He then briefly discusses general principles of fencing and of the weapons used. The remainder of the manual is dedicated to practical applications, and “if-then” sequences demonstrating the techniques in action. Although each illustration only depicts a scene from a single sequence, Capo Ferro uses the text to explain how that base sequence can be altered, sometimes in several ways, to produce different outcomes. Kirby presents the text as-is, with no glosses or commentary of his own on the techniques. Presenting his translation of the text side-by-side with that in the original language may have proven useful to many, but it is possible that this was not seen as necessary for Kirby to accomplish what he intended with the work.

Kirby’s decision to keep technical terms in the original language within the translation proves, if readers will forgive the expression, a double-edged sword. On the one hand, leaving the original terms in place allows for multiple interpretations to be formed from the text. Taking Kirby’s interpretation from the glossary, readers are free to apply different definitions of those terms to see whether or not they are suitable. On the other hand, the occurrence of an obscure Italian term, whose definition is not common knowledge, in the midst of an English sentence, can prove jarring to read at times.

In a similar vein, Kirby states in his introduction that he chose to provide as literal a translation as possible, rather than attempt much modernization of the wording, so as to better preserve the flavor and character of the text. This is accomplished, at times, at the expense of clarity and accessibility as antiquated Italian is rendered into a likeness of antiquated English. If the goal is to emulate the early English translations of Italian works, such as Saviolo’s His Practise of 1595, then this choice can work. However, if the goal is to provide an edition of this text that is accessible to as wide a modern readership as possible, then this aesthetic choice might not contribute productively to that effort.

An edition such as this can have one of three primary aims: to attempt to present the translated work in an objective manner that allows readers to make their own interpretations, to present the translated work in light of the editor’s own interpretations, or, most ambitious, to attempt to strike a balance between the previous two, with the editor giving their own interpretation but providing sufficient neutral data so as to allow others to draw differing conclusions. Kirby does not seem to specify which of these he intended, neither can one make a strong inference from reading, so it is hard to gauge his success.

What is most important, however, is that we finally have an English translation of this important work widely available to the public. Kirby has succeeded in setting the ball rolling on what will doubtless be a long and fruitful dialogue in the fight scholar community about translating and interpreting Capo Ferro. His years of work have paid off, resulting in a text that will prove a valuable asset to scholars and practitioners of Renaissance fencing in Europe.

James Hester

Independent Scholar ([email protected])