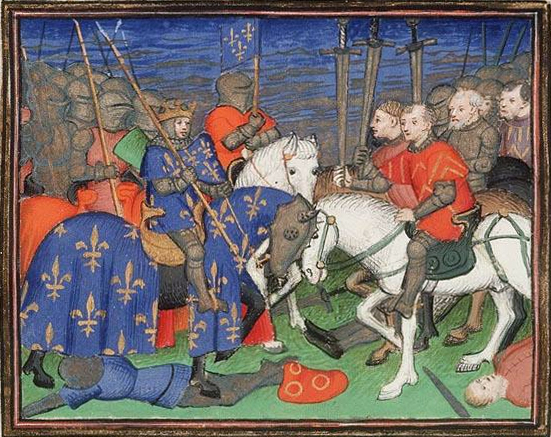

On July 12, 1214, Philip II Augustus, the King of France, defeated the combined forces of emperor Otto IV, the count of Flanders, and King John of England, near Bouvines in northern France.

The Marchiennes account of the Battle of Bouvines

The Relatio Marchianesis de Pugna Bouvinis was probably one of the first accounts of the battle to be written after the event. Marchiennes is a monastery close to Bouvines.

In the year of our Lord 1214, on the sixth calend of August, something worthy of remembrance occurred at the bridge of Bouvines, in the confines of the Tournaisis. In this place, on one side, Philip, the noble King of the Franks, had gathered a part of his kingdom.

On the other side Otto who, having persisted in the obstinacy of his wickedness, had been deprived of the imperial dignity through the decree of the Holy Church, and his accomplices in wickedness, Ferrand, Count of Flanders, and Renaud, Count of Boulogne, many other barons, and also those receiving a stipend from John, the King of England, had assembled in order, as the events were to show, to fight against the French. Driven by insatiable hatred, the Flemings, in order to recognize each other more easily, had, while preparing themselves to attack the French, sewn a small sign of the cross on the back and front of their coats of arms.

But it was much less for the glory and honor of Christ’s cross than for the growth of their wickedness, the misfortune and harm of their friends, the misery and damage of their bodies. This was clearly shown by the outcome of the battle. Indeed, they did not remind themselves of the sacred precept of the Church which states: “The one who communicates with an excommunicate is excommunicated.”

Persisting in their alliance with Otto who, by the judgment and authority of the Pope, had been bound into anathema and had been separated from the faithful of the Holy Mother Church, they were mocking this sentence with impudence and dishonesty. Inflamed by cruelty, they were planning while boasting with each other to reduce to nothing, if they could, the scepter and the crown of royal dignity: However, divine mercy and compassion which everywhere saves and protects its own, disposed of the matter differently. Philip, the very wise king of the Gauls, troubled by the imminent danger he saw his army facing, decided in a prudent and discreet council to withdraw himself and his people from the enemy’s aggression if lie could. He gradually retreated.

However, seeing that his adversaries were pursuing him terribly, like enraged dogs, and also bearing in mind that he could not retreat without too much dishonor, he put his hope in the Lord; he arranged his army into military echelons as is customary for those who are about to fight. But first, with a contrite heart, he addressed a prayer to the Lord. Then having called upon the noblemen of his army, he started to exhort them humbly, modestly, and with tears in his eyes: they should resist the adversaries with virility as their ancestors had been accustomed to doing, and so as not to suffer a loss that neither they nor their heirs could repair. These things, said with so much humility and earnestness, strongly warmed the hearts of his audience to act well and fight with virility.

As soon as the order of the royal power was heard in the army, tile knights and the auxiliaries, armed and arranged into ordered echelons, prepared ill all haste for the battle. The horses’ bridles were tightened by the auxiliaries. The armor shone in the splendor of the sun and it seemed that the light of day was doubled. The banners unfolded in the winds and offered themselves to the currents; they presented a delightful spectacle to the eyes. What then? The armies, thus ordered for battle on each side, entered into combat, full of ardor and desire to fight. But very quickly the dust rose toward the sky in such quantities that it became hard to see and to recognize each other. The first French echelon attacked the Flemings with virility, breaking their echelons by nobly cutting across them, and penetrated their army through all impetuous and tenacious movement.

The Flemings, seeing this and defeated in the space of all hour, turned their flacks and quickly took to flight. At this perilous moment, dependants abandoned to distress their lords, their fathers, their sons, and their nephews. However, Ferrand, Count of Flanders, and Renaud, Count of Boulogne, remained in the battle and resisted the onslaught of the French with virile fighting. In the end, they were wounded and taken by the French along with innumerable nobles whose names we will not give; they were jailed in a number of castles in Gaul.

As for Otto who, by the authority of the Pope, we refrain from calling Emperor, deprived of everyone’s help, thrown three times to the ground from his horse, or rather his horses as some claim, almost alone except for a single count, he hurried to take flight. Thus, surreptitiously fleeing from the King of France’s hand, he escaped, vanquished in battle. In this manner, the providence of divine mercy ended this battle which had been fought, as we have said, near the bridge of Bouvines, for the praise and the glory of His Majesty, and for the honor of the Holy Church. May its honor, its virtue, and its power remain through the infinity of centuries to come. Amen.

The Battle of Bouvines according to the Anonymous of Bethune

This account comes from a chronicle for the years 1185 to 1217 that was written after 1220 for Robert of Bethune, a participant in the battle, by a member of his entourage.

These are the names of the high men who went to battle with the King of France: Eudes, Duke of Burgundy; Henry, Count of Bar; Henry, Count of Grantpre; John, Count of Beaumont; Gauthier of Chatillon, Count of Saint Pol; William, Count of Ponthieu; Ainoul, Count of Guines; Raoul, Count of Soissons; Mathew of Montmorency; William des Barren; Engourans of Couchy and his two brothers Thomas and Robert, and many other great men too numerous to name.

The King of France went to his town Tournai, while the Emperor along with a castellan, Everard Radol, Castcllan of Tournai which he held from Count Ferrand, went to Mortagne. When the King of France heard that they were so near him, he became worried as Mortagne is only three mils from Tournai. Then he called his great men and concluded in council that they would go towards France the next day.

When the next day came, the king had all his men arm themselves and his echelons put in formation. He thus left Tournai and took the road to Lille with his host in good order. They were going so fast that all those who saw them said that they had never seen such a great armed host riding at such a speed. And when the Emperor and the Count Ferrand and the people who were at Mortagne found this out, what did they do? They climbed in full armor on their horses and rode at breakneck speed after them so as to catch up with their prey. They reached the Duke of Burgundy and the Champenois who made up the rearguard in a small wood two miles away from Tournai and pressed them so hard that they had to stop and turn toward them and had their bowmen shoot so as to make their men [the assailants] retreat. In this manner, the Flemings forced the rearguard to stop five times on this day and turn towards them, so that the Duke of Burgundy sent a message asking the King to ride slowly as they were much, pressed.

Brother Guerin came to the King at a church called Bouvines, near Cysoign, which the Queen had once visited. He found him off his horse at a place where he had refreshed himself with bread and wine. He asked him: “What are you doing?” “Well,” said the King, “I have eaten.” “That is good,” said Brother Guerin, “and now you need to arm yourself because those on the opposite side do not, on any account, want to postpone the battle till tomorrow but they want it now. Thus you must do likewise.”

It was Sunday, and because of this the King would have preferred the battle to be postponed till the morrow for the honor of the day. But when he saw that there was no other way, he put on his armor, entered the church, made his orisons, and was soon finished praying. Then he climbed on his horse and did not appear frightened anymore as he decided and ordered his affairs very wisely and assuredly and without any panic, and had everyone, knights and others, called to return to their battalions. I must tell you that most of the host had already passed a bridge spanning a small river and several pavilions had already been set upon the other side of the bridge in a meadow where the King had planned to spend the night.

Thus the King had his echelons put in formation and they rode forward. You could see among them many noblemen, much rich armor and many noble banners. The same was true for the opposite side, but I must tell you that they did riot ride as well and in as orderly a manner ac the French, and they became aware of it.

As the hosts had come close enough to see each other clearly, they stopped for a long time and put their affairs in order. Then the king asked for an echelon of mounted sergeants, who were all carrying pennants at the tips of their swords, to assemble, and they did. They attacked the Flemings and performed many great deeds.

Before anything else notable occurred, Arnoul, the Castellan of Rasse, let his horse loose between the two lines and charged their bowmen, sending them running and throwing one to the ground; then he charged the knights and in his drive threw rudely to the ground a bachelor named Michel of Auchi and kept on going through, and then came back safe and sound to his people where he was much praised.

Then the Count of Flanders charged the Champenois and the Champenois charged him and there was a heated melee, but the Champenois had to retreat.

Then, the Viscount of Melun charged; in his battalion were the Count of Ponthieu, the Count of Guines, and all those residing between the Somme and the Lis who had come from the fief of Louis, the King’s son. This battalion stopped the pursuit, and they all fought so well that the valorous men who were there said that they had never seen such good tourneying as had occurred during this battle.

Baudouin of Praet, a wealthy man from Flanders, with a blow threw Huan of Malaunoi [Hugh of Maleveine?], a very good knight, and his horse to the ground as he was charging him.

Then the armies from both sides charged each other and there was a melee. The King’s trumpets sounded because he himself had been hit and his horse fell under him, but he was soon up again. On this day, his banner was carried by Galon of Montigny, a knight from the Vermandois who carried it very gallantly.

Gauthier of Chatillon, Count of Saint-Pol, charged through the whole of the battalions and caused much damage. And when Henry, Duke of Louvain, who had not yet charged, saw this, he took flight and initiated the defeat.

When Count Ferrand was taken, the Flemings started to tremble and, one after another, began to take flight. Seeing this, the valorous men of France charged this battalion and gave grief to the Flemings and the Emperor’s men even though these included many a noble baron.

Mathew of Montmorency held a billhook in his hands and was astride a great horse. All those who saw him charge through the melee and saw how he went about, hitting and throwing knights to the ground and wounding many people, deny ever having seen a better knight.

Eudes, Duke of Burgundy, had put on the coat of arms of William des Barres, the good knight, but carried his own shield. You must know that he [William] had performed so many great deeds of arms that he was spoken about with praise as far away as Syria. He [the Duke of Burgundy] looked to one side and saw Arnoul of Audenarde, one of the greatest men of Flanders and, since his youth, one of the best knights, at a spot where he had stopped in front of the sergeants. And thus he charged him. When Arnoul saw him coming, he told his people: “Lords, look, William des Barres, the good knight, is charging us. Let us make our horses face toward him because if he attacks us from the side he would do us too much harm.” He was saying this because he thought that the duke was William des Barres on accountt of the coat of arms that he was wearing. As he uttered these words, the duke came upon him and Arnoul stood his ground well and bravely. As they fought each other, the duke bent down and tried to slay his horse but Arnoul had a knife in his hand and tried to hit the duke through the eye-hole of his helmet but the duke bent down and parried the blow, and then fled. And when Arnoul saw him leave, he told his squire who was called Estoutin: “God helped us!” Estoutin said: “He could help us some more and make their good knights leave instead of ours abandoning this place.” But things were not to go the way he wished. And thus there were clashes everywhere and they did what they knew how to do well. There was fine prowess and passage of arms.

What more call I tell you? The Emperor’s men and those of Count Ferrand were completely defeated. Count Ferrand himself was taken, as I told you, with many great men from his land. Hellins of Waverin, the Seneschal of Flanders, a fairly new knight, was taken. The three sons of Rasson of Gaure, the boteillier of Flanders – Rasse the eldest who was very brave for his age and his two brothers, Arnoul and Philip ‑ were taken. Gerard of Grinberghes, who was also a very brave man, was taken. Gauthier of Ghistele and Philip of Malenghin, who had much valor, and Peter del Maisnil, a young man, the son of the good Pieron del Maisiiil who was both valorous and wise, were taken. Robert of Bethune was taken but he offered so much to a knight called Fleming of Crepelaine that he freed him and brought him back to safety.

From amongst the King of England’s people William Longsword, Count of Salisbury, brother of the King of England, was taken.

Renaud of Dammartin, the Count of Boulogne, and several other knights with these two counts were taken.

From among the Emperor’s people Count Hairy and Bernard of Ostemale, a very good knight, and Conrad of Tremoigne, a man of great worth, and several others were taken.

Arnoul of Audenarde, who was Flemish, was also taken but the King soon turned him over to the Count of Soissons whose cousin he was and to Roger of Rassoi whose daughter he had wed. In the evening, the Duke of Burgundy mentioned this and said to the King: “You have the right to ransom him because if it were not for him you would have 200 more knights in your prisons.” And the King answered the duke: “Duke of Burgundy, I am well aware of this! But he never did like war and he always advised his lord against it; he has never wanted to do homage to the King of England when the others did so; if he has done me wrong in order to loyally serve his lord, I hold no ill will toward him on that account.” Thus the King did honor to Arnoul of Audenarde.

What more can I tell you? It was a marvel that the number of barons, bachelors, sergeants taken was so great. They were pursued over two miles of land. The emperor took flight towards Valenciennes, and spent the night at the Abbey of Saint-Sage, and the others ran away to various places as best as thoroughly vanquished people could.

And the King returned to France with the whole of his host and his prisoners. He put the Count of Boulogne in the tower at Peronne, and the others he brought to Paris. He put the Count Ferrand along with Eustache del Roes, a great man from Hainaut, in prison in the tower of the Louvre where many a great man and traitor was kept. And most of the others he put in prison in the fort of the Great Bridge and the others he put in the fort of the Little Bridge. In this way, he kept them a long time and received large ransoms for several of them and, as you might guess, none escaped.

After this, no one dare wage war against him, and he lived in great peace and the whole of the land was in great peace for a long time to come so that his bailiffs could exact much and his son’s bailiffs even more from all the land he had come to hold: it was one of his sergeants called Nevelon, who was bailiff of Arras, who put into such servitude the whole of Flanders, inherited by Louis, that all those who heard about it marveled that one could suffer so and endure.

This Battle of Bouvines occurred on a Sunday, in the month of July, in the year of our Lord One Thousand Two Hundred and Fourteen.

[smartads]

The Battle of Bouvines according to the Philippiad, by William of Breton

The Philippiad is rhymed elaboration of William the Breton’s continuation of the Gestes de Philippe Auguste. William was a chaplain to the French king, and was present on the battlefield of Bouvines.

Song X, verses 755-838

. . . He says [these things] and runs to the King. He [the King] can scarcely believe that someone would dare initiate a battle on this holy day which God himself has specially consecrated to himself alone. The King nonetheless suspends the march, gives orders for the banners preceding him to stop, and addresses his friends as follows: “Now, the Lord Himself is giving me what I wanted; now, beyond our merits and our hopes, divine favor is granting us more than all our wishes. Those we were previously trying to reach through long detours and the many turns of the roads, the Lord’s mercy has brought to us, so that He Himself could, through us, destroy His enemy in one blow. With our swords He will cut off the members of His enemies; He will turn us into cutting instruments; He will hit and we will be the hammer; He will lead the whole battle and we will be His ministers. I have no doubt that victory will be His, that He will triumph through us, that we will triumph through Him over His own enemies who bear Him so much hatred. Already, they have deserved being struck with the sword of the father of fathers [because] they have dared to despoil Him, to deprive the Church of its property, to take away the small coins [les sous] with which the clergy, the monks, and God’s poor were sustaining themselves and whose curses are now causing their damnation, and will keep on doing so, and whose laments rising to the heavens will force them [the enemy] to succumb to our blows. In contrast, the Church is in communion with Lis and assists us with its prayers and everywhere recommends us to the Lord. Everywhere, the clergy prays for us with an ardor that is even greater than our love for them. This is why, strengthened with the unbreakable power of hope, I am asking you to show yourselves to be the enemies of the enemies of the Church. May your fighting prevail, not for me but for you and the kingdom; may each of you, while protecting the kingdom and the crown, take care also not to lose his own honor. However, my wish for battle is less than my reluctance to sully this holy day with the spilling of blood.”

He said this and the French, through a long joyous cry, make known that they are ready to fight for the honor of the kingdom and the King. However, they are all of the opinion that they should go to Bouvines to see if the enemy will not choose to respect the holy day and to postpone the duel till the passing of the day would make the battle lawful. Moreover, this position would be a better one for the defense of the baggage and all the other things carried in order to set up camp, in view of the fact that it is only open to one side and that the marsh, lying without break to the right and the left, intercepts the road and makes crossing impossible except through the fairly narrow bridge of Bouvines on which quadrupeds and bipeds can go toward the south. On the far side lie fields and a beautiful plain, abloom with Ceres’ grains, and which, continuing over a large area, reaches Sanghin on the west and Cysoing on the east – a place well suited to be sullied with blood since these names recall blood and killing.

Right away, the King has the bridge enlarged so that twelve men could cross abreast of each other and so that the wagons with their four horses could cross it with their drivers. Near a church consecrated to Peter, the King, hot from the sun, hoping that the battle would be postponed till the morrow, was resting in the shade of an ash-tree, not far from the bridge which had already been crossed by the main part of the army, while the sun, having reached its highest point, was heralding the middle of the day. While the King was getting ready for a short rest, a swift messenger, arriving in all haste, exclaimed: “The enemy has already charged the rearguard; neither the troops from Champagne, nor those which you have sent earlier are able to repulse them: while they are resisting and do their best to slow them down, [the enemy] pushes forward and has already traveled two miles.”

Moved by these words, the king immediately stands up, enters the church, and places his arms under the protection of the Lord. After a short prayer, he comes out: “Let us go,” he exclaims. “Let us go in all haste to help our companions. God will not be angry if we take up our arms at a holy time against those who are attacking us. He has not found the Maccabees guilty of any crime for having defended themselves during a holy Sabbath when they repulsed the forces of their enemies with a holy victory. Even more so, it is seemly for us to fight on this day when the whole of the Church begs the Lord on our behalf and we are proving ourselves to be its friends.” Speaking these words, he puts his armor on, throws his tall body on his tall horse, and, retracing his footsteps, hurries toward the enemy while the terrifying din of the trumpets is heard all around him . . . .

Song XI, verses 20-46

Soon after, Otto, already flying his banners as if he wanted to celebrate before the fact the triumph he was so sure of, raises his standard high, surrounds himself with the supreme honors of the empire, so as to make his rays shine in the middle of such a great show and to proclaim himself the sovereign of the whole world. On a chariot, he has a pole raised around which a dragon is curled which can be seen far away from all sides, its tail and wings bloated by the winds, showing its terrifying teeth and opening its enormous mouth. Above the dragon hovers Jupiter’s bird with golden wings while the whole of the surface of the chariot, resplendent with gold, rivals the sun and even boasts of shining with a brighter light.

As to the King, he is content to see lightly fly his simple banner, made of a simple silken cloth of bright red and in every way similar to the banners usually used in church processions on prescribed days. This banner is commonly known as the Oriflamme: it has the right to be carried in all battles, ahead of every other banner, and the Abbot of Saint-Denis has the custom of handing it over to the king whenever he takes up his arms and goes to battle. The royal banner was carried ahead of the King by Galon of Montigny, a man of strong body. Thus the two armies found themselves face to face; the portion of plain separating them was narrow; they were lined up face to face, but one could not yet hear the Sound of any voice.

Placed on the other side and opposite the magnanimous Philip, Otto was covered with gold and clothed with the imperial ornaments ….

Song XI, verses 53-64

. . . On the right side and at a great distance from the King, the Champagne corps threatens the men of Flanders. With them [the Champenois] are the Duke of Burgundy, the Count of Saint-Pol, John of Beaumont, and the men sent by the Abbot of Saint‑Medard, retainers famous on account of their great prowess, and who numbered 300. Each of them, mounted on a horse, exulted in his armor and brandished his sword and lance; they were from the valley of Soissons which produces strong bodies. Between them and the King was placed a continuous line of men, splendid in valor, and each of their leaders called their echelons close to them while the trumpets sounded terrifyingly, inviting the warriors to promptly charge the enemy . . .

Song XI, verses 116-32

. . . While Ferrand in fighting; arouses courage in his men, lances are shattering, swords and daggers hit each other, combatants split each other’s heads with their two-sided axes, and their lowered swords plunge in the bowels of the horses when the iron protection which covers the bodies of their masters prevents iron from penetrating; then. Those who are carried then fall with those carrying; them and become easier to vanquish when they are thus thrown to the dust. But even then, iron cannot reach them unless their bodies are first dispossessed of the armor protecting; then, so much has each knight covered his members with several layers of iron and enclosed his chest with armor, pieces of leather and other types of breastplate. Thus, nowadays, modern mere take much greater care tee protect themselves than did the ancients who would often, as we learn from our reading;, fall by the thousand in a single day. While misfortunes multiply, precautions against these misfortunes multiply as well, and new defenses are invented against new kinds of attack . . . .

Song XI, verses 178-99

. . .The irruption of the combatants is so lively all over the field and those who are hitting or are hit are so close to each other that they can barely find the place or the opportunity to stretch their arms so as to strike more strongly. The silk coverings attached to the top of the armor so that everyone could be recognized by these signs have been so cut tip and ripped into a thousand shreds by the maces, swords, and lances which are pounding on the armor so as to break it that each combatant call barely distinguish his friends from his enemies. One is lying on the ground, overturned on his back with his legs in the air, another falls on his side, a third is thrown head first and his eyes and mouth fill with sand. Here a cavalryman, there afoot soldier voluntarily surrender, fearing more to be killed than to live vanquished. You could see horses here and there lying in the meadow and letting out their last breath; others, wounded in the stomach, were vomiting their entrails while others were lying down with their hocks severed; still others wandered here and there without their masters and freely offered themselves to whomever wanted to be transported by them: there was scarce a spot where one did not find corpses or dying, horses stretched out . . . .

Song XI, verses 538-58

. . . Indeed, the Bishop of Beauvais, having seen the brother of the King of the English, a man of incredible strength whom the English had on this account nicknamed “Longsword,” overthrow the men of Dreux and do great harm to his brother’s battalion, the bishop became unhappy, and since by chance he happened to have a mace in his hand, hiding his identity of bishop, he hits the Englishman on the top of the head, shatters his helmet, and throws him to the ground forcing him to leave on it the imprint of his whole body. And, since the author of such a noble deed could not remain unnoticed, and since a bishop should not be known to have carried arms, he tries to hide as much as possible and gives orders to John, whom Nesle obeys by the right of his ancestors, to put the warrior in chains and to receive the prize for the deed. Then the bishop, throwing down several more men with his mace, again renounces his titles of honor and his victories in favor of other knights so as not to be accused of having done work unlawful for a priest, as a priest is never allowed to be present at such encounters since he must not desecrate either his hands or his eyes with blood. It is not forbidden, however, to defend oneself and one’s people provided that this defense does not exceed legitimate limits . . . .

Song XI, verses 585-718

. . . While flight had entirely emptied the field of battle on both wings, the Count of Boulogne still remained in the center, frequently retreating into the midst of his foot soldiers, furiously and ceaselessly striking with his murderous sword the breasts of his friends and kill. Enemy of his friends and hating the children of his fatherland, neither the tie to his native land nor the love owed to those sharing the same blood, nor the ties of a friendly flesh, nor the pledges sworn so often to his King and lord, had softened his heart hardened by [spilled] blood. His unbridled valor did not allow anyone to vanquish him; it did not matter whom his arm reached, he could [always] walk away the winner, so well could he handle weapons with ability and prudence, so much the prowess which was natural to him in battle loudly proclaimed that he was the true issue of French parents: And even though his fault itself has, oh France, made him fall in your eyes, do not be ashamed of him and do not let your brow blush. Not only are children not cause for shame to those who give them birth but, moreover, it often happens that a good mother puts depraved children into this world and also often a wicked mother nurses healthy children at her breast.

The count kept on retreating with impunity behind the wall of his foot soldiers; he did not need to fear being hit with a mortal blow by the enemy. Indeed, as our knights were fighting on their own with their swords and their short weapons, they would have feared attacking the foot soldiers equipped with lances: these, with their lances longer than knives and swords, and moreover lined up in an unbreachable formation of triple layers of walls, were so cleverly disposed that there was no way that they could be breached. The King, having recognized this, sent against them 3,000 armed retainers mounted on horses and equipped with lances so as to make them abandon their position by putting them in disorder, and thus to free himself of this formidable ring. A clamor then arises; the cries of the dying, the noise of arms make it no longer possible to hear the sounds of the trumpets. They fall, riddled with wounds, all of these unfortunate people with whom the Count of Boulogne had surrounded himself with an art now useless, believing in vain that he could defy all the French by himself, caring to keep on fighting them after all the others had run away and disdaining owing his life to a shameful flight.

These unfortunates could no longer be protected by their long weapons, or their two-sided axes, or by the count who was no longer able to defend his wall. Nothing could then prevent valor from reaching its goal; alone, valor finally overcomes all obstacles; no resistance, nee artifice, »o force can resist it; alone it provides everything and rises above everyone. It rejoices in being the intimate companion of the French, it finally grants them the full enjoyment of their triumph. They massacre all their enemies, send them all to Tartarus and completely take away from the Count of Boulogne the sanctuary he had made for himself. As for him, however, having seen the field flooded on all sides with fugitives so that there barely remained around him thirty men, knights and foot soldiers, the remnants of the whole of his troop, and so that no one could believe that he was willing to let himself be taken or vanquished without resistance, he throws himself in the midst of the French, followed by only five of his companions, while the French surround all the others and barely find enough room within their tight ranks to bind them. Then the count, as if he had to triumph alone over all his enemies and as if he had not yet engaged in any combat on this day, furious and using of the whole of his strength and multiplying his efforts, rages in the middle of the French and hurries through them towards the king, having no doubt that he will take his life as prize for his own death, and wishing only to die at the same time as him.

A certain Peter, whom La Tournelle had given both his name and his distinguished birth, was on foot having lost his horse while the count was audaciously throwing himself into the ranks of his enemies. This man, deserving by his origin and his exploits to become a knight, was both beloved and well known at the King’s court. Seeing that the Count of Boulogne had taken up the fight again without wanting to surrender and was even resisting all those around him with renewed valor, Peter quickly went toward him, lifted up with his left hand the wire mesh which, tied with large strips, covered the belly of the horse, and with his right hand, thrusting his sword into the body of the horse at the groin, cut his noble parts. Then he pulled out his sword and the blood flowed abundantly from a large wound and covered the green grass. At this sight, one of the loyal friends of the count ran up to him and, quickly grasping the reins of his horse, heatedly addressed words and friendly exhortations to the count himself who, disregarding God’s will and while all the others had taken flight, still remained there, attempting to vanquish all by himself those who were the victors, thus provoking his own destruction through such behavior and not fearing to throw himself into well-deserved ruin when it would be easy to escape it by fleeing with the others. While he was addressing the count with these words, he drags him in spite of himself by pulling his horse by the bridle, so as to make him climb on another horse and be able to flee. But the count resists with all his might, his proud heart not being capable of ever renouncing the battle: “I would rather,” he says, “be vanquished while fighting and saving my honor than live by running away. Life is not worth [the loss of] honor. I am going back to the battle, regardless of the fate which threatens me.”

He says this but already his horse has felt his nerves slacken and can no longer stand. Then John of Condone and his brother Quenon run up to him and hit the count with many blows on each side of his head and throw down both horse and knight; they both fall head first, and then the count lies on his back, his thigh trapped and crushed under the full weight of the horse. While the two brothers busy themselves in binding the cavalier, John, nicknamed “de Rouvrai” (de Robore) [“strong”], a name which facts justify, appears and finally forces the count to surrender in spite of himself. And as he was slow in getting up from the ground, waiting in vain for help and still hoping to escape, a boy [a commoner] named Cornut, one of the servants of the Elect of Senlis, and walking ahead of the latter, a man strong in body, arrives holding a deadly knife in his right hand. He wanted to cut the count’s noble parts by plunging the knife in at the place where the body armor is joined to the leggings, but the armor sowed into the leggings will not separate and open up to the knife, and thus Cornut’s hopes are thwarted. However, he circles the count and looks for other ways to reach his goal. Pushing the two whalebones out of the way and soon pulling off the whole of his helmet, he inflicts a large wound upon his unprotected face. He was already getting ready to slit his throat; no one was holding him back and if it had been possible he would have killed him. The count, however, still resists him with one hand, and does his best to repulse death as long as he can. But, finally arriving at a full gallop, the Elect of Senlis pushes the threatening knife away from the count’s throat and himself pushes away the arm of his servant. Having recognized him, the count cries: “Oh, kind Elect, do not let me be assassinated. Do not suffer me to be condemned to such an unjust death, so that this boy could rejoice to be the author of my destruction. The King’s court would condemn me much better; let it inflict on me the punishment I have incurred.” He says this and the Elect of Senlis answers him in these words: “You will not die, but why are you so slow to get up? Stand up, you must be presented to the King right away.”

While saying this, he forces the wounded man to stand up in spite of himself. His face and all his members are covered with a stream of blood; he can barely lift his body to climb back on a horse; the Elect of Senlis places him on it and everyone applauds, as he still scarce appears to be vanquished. The Elect finally entrusts him to the care of John of Nesle to go and offer this pleasing gift to the King ….

Song XII, verses 18-50

. . . Here, one man grabs a war-horse; over there, a big cob offers its head to a stranger and is tied with a rope. Others take abandoned weapons from the fields; one grabs a shield, another a sword or a helmet. Another one leaves happy with leggings while yet another is pleased with a breastplate and a third gathers clothing and armor. Yet even happier and in a better position to withstand the vagaries of fortune is the one who can seize the horses laden with baggage or the swords hidden under their bulging sheets, of again these wagons the Belgians are said to have been the first to build in the olden days when they possessed the Empire: these wagons are filled with golden vessels, with all kinds of implements which are not to be disdained, and with silken clothing worked with great art which the merchant transports to our country from far away places seeking in his greed to multiply his petty profits on any object. Each of these wagons, supported by four wheels, is topped by a chamber which in no way differs from the superb nuptial chamber where a newly wed bride is preparing for a new union, so many are the possessions, food, and precious ornaments enclosed in the large belly of each of these chambers woven out of bright willow. Sixteen horses hitched to each of these wagons is barely sufficient to drag away the spoils with which they are laden.

As to the wagon on which the reprobate Otto had raised his dragon and over which he had hung his golden winged eagle, it soon falls under countless axe blows and is broken into a thousand pieces. It becomes the prey of flames as it is wished that no trace should remain of so much pomp and that pride thus condemned should disappear with all its marks of ostentation. The eagle whose wings were broken was promptly repaired. The king sent it immediately to King Frederick so that he would learn through this present that, since Otto had been repulsed, the fasces of the Empire had passed into his hands by divine favor ….

Song XII, verses 225-64

. . . At that time, only the city of Rome was offering applause to its kings and the other cities were not in the least concerned with rejoicing over the triumphs of the Romans or of going to any expense to add to the ceremonies. But now, in all places located in the land of the vast kingdom which contains so many villages, so many castles, so many cities, so many counties, so many duchies worthy of the scepter, in all the provinces submitted to so many bishops, each administering justice in his own diocese and publishing his edicts in innumerable towns, every town, every village, every castle, all the countryside feel with the same ardor the glory of a victory common to all, and take for themselves that which belongs to all in common, so that this universal applause spreads to all places and a single victory causes the birth of a thousand triumphs. Applause is heard everywhere throughout the kingdom: people from all social conditions, from all fortunes, from all professions, from all sexes, from all ages sing the same hymns of joy, all voices celebrate at once the glory, the praise, and the honor of the King. And the raptures of the soul are not only expressed through songs or in gesture: in the castles and in the towns, the trumpets sound in every street so that the multiplication of these choruses would proclaim public feelings louder. Do not think either that any expense is spared: knight, bourgeois, villein, all shine under the purple, they all wear clothing made only of samite, or very fine linen, or purple cloth. The peasant, resplendent in imperial adornments, is surprised at himself and dares compare himself to the mightiest kings. The clothes change his heart so much that he believes that the man himself is changed along with the unfamiliar clothing. And each is not simply content with shining as much as his companions, but he also attempts to distinguish himself from the mass of others by some ornament. Thus they all vie with each other, trying to surpass each other with the honor of their clothing.

During the whole night, candles ceaselessly shine in everyone’s hands, chasing away the darkness so that the night, finding itself suddenly transformed into day and resplendent with so much brilliance and light, says to the stars and the moon: “I owe nothing to you.”

This happened because love for the King was so great that it led the people in every village to give vent to the rapture of their happiness ….

The Battle of Bouvines according to Roger of Wendover

Roger of Wendover was an English chronicler, whose work the Flowers of History was completed between 1219 and 1225.

At this same time, the King of England’s army which was waging war in Flanders was causing devastation with so much success that, after having ravaged several provinces, it penetrated into the territory of Ponthieu and devastated it with an unrelenting fury. Those who took part in this expedition were valiant men, with great expertise in war, such as William, Count of Holland, Renaud, formerly Count of Boulogne, Ferrand, Count of Flanders, Hugh of Boves, a good knight but cruel and arrogant who struck with so much rage against this country that he spared neither the weakness of women nor the innocence of small children. King John had named, as marshal of this army, William, Count of Salisbury, to fight with the English knights and to disburse to the others payment taken from the treasury. These warriors received the help and the favor of Otto, Emperor of the Romans, with the troops that the Duke of Louvain and the Duke of Brabant had assembled. They were together attacking the French with equal fury. When news of this reached Philip, King of France, he was very pained as he worried that he did not have enough troops to defend this part of the land, having recently sent to Poitou his son Louis with a large army to repel the hostile incursions of the King of England. However, even though he often repeated to himself the common saying “The one who is busy with many things at once can less clearly judge each one of them,” he nonetheless gathered a large army made up of counts, barons, knights, and sergeants, on foot and on horses, and [militias] coming from the communes and the towns. Accompanied by these contingents, lie prepared to march against his adversaries. At the same time, he ordered the bishops, the clerks, the monks, and the nuns to distribute alms, to address prayers to God, and to celebrate the divine mysteries in favor of the kingdom. Having arranged this, he left with his army to fight his enemies.

He was told that his adversaries had advanced in arms tip to the bridge of Bouvines, in the territory of Ponthieu. He led his armies and his standards in that direction. When he arrived at the above named bridge, he crossed the river with the whole of his army and decided to camp in that place. Indeed, the heat was extreme because the sun is very hot in the month of July. Thus the French took up their position near the river to refresh their men and their horses. They arrived at that river on a Saturday, toward evening, and after having disposed, on the right and on the left, wagons drawn by two and four horses as well as the other vehicles which had carried the food, the arms, the machines and all the instruments of war, this army set up guards oil all sides and spent the night in this spot.

The next morning, when the princes of the King of England’s chivalry were told of the arrival of the King of France, they hurriedly held a council and unanimously decided for a battle champel. But since this day was a Sunday, the wisest in the army, and particularly Renaud, formerly Count of Boulogne, stated that it would not be very honorable to wage a battle on such a solemn day and to sully this day with homicide and the spilling of human blood. The Emperor Otto went along with this viewpoint and said that if he fought on such a day he could never boast of a joyous triumph. At these words, Hugh of Boves lost his temper and, cursing, called the Count Renand a despicable traitor, and reproached him for the lands and the large possessions that he had received from the King of England’s generosity. He added that the postponement of the battle to another day would bring irreparable damage which would harm King John and that one always has cause to repent when one has not grasped a favorable opportunity. Renaud answered Hugh with indignation: “This day will prove that it is I who is loyal and you who are a traitor; because on this Sunday I will, if need be, fight to the death for the King while you, as usual, on this same day, you will show to all by running away that you are the evil traitor.” These insulting words provoked by Hugh of Boves’ similar words, soured everyone’s spirits and made the battle unavoidable. The army ran to its arms and formed into ranked battalions. When they were all armed, the allies divided themselves into three battalions: the first had as captains Ferrand, the Count of Flanders, Renaud, Count of Boulogne, and William, Count of Salisbury; the second was led by William, Count of Holland, and by Hugh of Boves with his Brabancons; the third was made up of German soldiers under the command of the Roman Emperor Otto. In this order, they marched slowly toward the enemy and arrived at the French.

King Philip, seeing his adversaries ready for a battle champel, had the bridge which was behind his army destroyed so that if, by chance, some of his soldiers should attempt to flee they could only open up a way through the enemies themselves. The King, after having arranged his troops in the area delimited by the wagons and the baggage, awaited the shock of his adversaries’ attack. Finally, the trumpets sounded on both sides and the first battalion, in which the counts we have spoken of were, threw itself so violently on the French that in a moment it broke their ranks and penetrated to where the King of France stood. Count Renaud, who had been disinherited and chased away from his county by the King, saw him, struck him with his lance, threw him to the ground, and tried to kill him with his sword. But a knight who, along with many others, had been assigned to protect him [the King], threw himself between him and the count and received the mortal blow. The French, seeing their King on the ground, hurried towards him, and a large troop of knights put him back on his horse with some difficulty. Then the battle was engaged on all sides; swords threw lightning flashes by falling like thunder on the helmeted heads and the melee became furious. However, the counts we have mentioned, along with their battalion, found themselves too far removed from their companions and noticed they could not join their allies and the latter could not reach them. Because of this, not being able to withstand the superior forces of the French, they were overwhelmed by their numbers and the above named counts along with the whole of the battalion were taken and put in chains after very great prowess and having killed a large number of the enemies.

While these things occurred around King Philip, the Counts of Champagne, of Perche, and of Saint-Pol, along with many nobles of the kingdom of France, attacked in their turn the other two battalions and put to flight Hugh of Boves along with all the people who had been recruited in various provinces. While they were running away like cowards, the French, with their swords drawn, pursued them all the way to the place where the Emperor stood. Then the whole of the weight of combat became concentrated on that spot: The above named counts surrounded the Emperor and tried to kill him or to force him to surrender. But he, with his single-edged sword, which he held with both hands like a billhook, was dealing unfendable blows all around him. All those he struck were stunned or fell to the ground along with their horses. The enemies, fearing to come too close, killed three horses under the Emperor with lance blows. But always the praiseworthy prowess of his companions put him back on a new horse and he threw himself anew against his enemies. Finally, the French let him go. Unbeaten, he left the battle along with his people with no harm to him or his followers.

The King of France, happy with such an unexpected victory, gave thanks to God who had granted him such a great triumph over his adversaries. He brought with him, laden with chains and destined to be locked in strong prisons, the three aforementioned counts as well as a numerous crowd of knights and others. When the King arrived, the whole of Paris was illuminated with torches and lanterns, resounding with songs, applause, fanfares, and praises during the following day and night. Carpets and silken cloths were hung from the house; the enthusiasm was general.

The Battle of Bouvines according to William the Breton (prose account)

William the Breton was the personal chaplain and advisor to the French king Philip Augustus, and was present on the battlefield of Bouvines when the French forces under Philip defeated the German emperor Otto. His account, although very favourable to the French king, is very detailed and clear, allowing the reader a good understanding of the what occurred during the battle.

And now we would like to write as best we can of King Philip’s glorious victory.

In the year of Our Lord 1214, at the time when King John of England was warring in Poitou, as we have said earlier, and that he fled, him and the whole of his host, at the approach of My Lord Louis, Otto, the damned and excommunicated Emperor whom King John of England had retained against King Philip, assembled his host in Hainaut at the castle of Valenciennes, in the land of Count Ferrand who had allied himself against his liege lord. There King John sent to him, at his expense and in his pay, noble combatants and knights of high valor: Renaud the Count of Boulogne, William Longsword, Count of Chester, the Count of Salisbury, the Duke of Limburg, the Duke of Brabant who had wed Otto’s daughter, Bernard of Ostemale, Othe of Tecklemburg, the Count Conrad of Dortmund and Gerard of Ramrode, and many other counts and barons from Germany, Brabant, Hainaut, and Flanders. The good King Philip assembled on his part his chivalry at the castle of Peronne, only as much of it as he was able because his son Louis was warring at that time in Poitou against King John and had with him a great part of France’s chivalry.

On the day after Magdalen day, the King left Peronne and entered in great strength into Ferrand’s land; he went through Flanders while burning and destroying everything left and right and in this manner arrived at the city of Tournai which the Flemings had taken by trickery the previous year and damaged badly. But the King sent Brother Guerin and the Count of Saint-Pol to the city and they took it back quite easily. Otto left Valenciennes and went to a castle called Mortagne. This castle was taken by force and destroyed by King Philip’s host after they had taken Tournai which was only six miles away.

The first week after the feast day of Saint Philip and Saint James, the King proposed attacking his enemies, but his barons advised him not to, as the passes to them were narrow and difficult to cross. Because of this, he changed his mind on the advice of his barons and ordered that they backtrack and find a more level way into the county of Hainaut and destroy it completely. The following day, which was thus the sixth calend of August, the King left Tournai and was longing to rest himself and his host that same night in a castle called Lille. But things went differently than planned as Otto had left the castle of Mortagne that same morning and, as hard as he could, rode after the King in battle order. The King neither knew nor thought his enemies were thus coming after him. It so happened by chance or by the will of God that the Viscount of Melun along with other lightly ‘armed knights detached himself from the King’s host and rode toward those parts from which Otto was coming. And, detached also from the host and riding with him was Brother Guerin, the Elect of Senlis (Brother Guerin, we call him, because he was a practising brother of the Hospital and still wore its habit), a wise man, of sound counsel and with marvelous foresight for things to come. These two went away from the host for about three miles and rode together till they climbed a high hill from which they were able to see clearly their enemies’ battalions moving fast and in fighting formation. When they saw this, the Elect Guerin left immediately and made haste to return to the King, but the Viscount of Melun remained on the spot along with his knights who were rather lightly armed. As soon as he reached the King and the barons, the Elect Guerin told them that their enemies were fast arriving in battle order and that he had seen the horses covered, the banners unfurled, the sergeants and the foot soldiers up front which is a sure sign of battle.

After the King heard this, he ordered the whole host to stop and then convened the barons and sought advice on what to do, but they did not much favor waging battle and advocated riding on. When Otto and his people came to a small stream, they crossed it a few at a time because the passage was difficult. After they had alt crossed to the other side, they pretended to go toward Tournai. T hen the French started to say that their enemy was going away towards Tournai. But at that moment Brother Guerin felt the very opposite and cried and insisted with conviction that the thing to do was to fight or to retreat in shame and loss. Finally the opinion of the many prevailed over that of the one. They continued on their way and rode thus to a small bridge called the bridge of Bouvines, between the place named Sanghin and the village called Gisoing. The greater part of the host had already crossed the bridge, and the King had taken off his arms but had not yet crossed the bridge, as his enemies believed. Their plan was, had the King crossed the bridge, to throw themselves on those whom they found crossing it and kill them or take them prisoner.

As the King was resting for a while in the shade of an ash-tree because he was already quite worn out as much from riding as from bearing his arms (quite close to this place was a small chapel founded in honor of My Lord Saint Peter), messengers of those who were in the last battalion came to the host. Horrified, they were yelling with terrible cries that their enemies were coming and were readying to wage hard battle on those who were in the last echelon, and that the Viscount of Melun and those with him who were lightly armed and the bowmen who were containing the enemy’s arrogance and bearing his assault were in great danger and could not restrain for very long his temerity and forcefulness. Then the host started to become excited and the King entered the chapel of which we spoke above and offered a short prayer to Our Lord. After coming out, he had himself hastily armed and he jumped on his steed, as lively and in as great spirits as if he had been on his way to a wedding or a celebration to which he had been invited. Then the cry “To arms, barons! To arms!” was heard in the fields. Trumps and trumpets began to rise up and the battalions which had already crossed the bridge began to return. The Oriflamme of Saint Denis which was carried at the front line of the battle, ahead of all others, was then called back. But so that it would not have to return in haste, it was not awaited as the King at full gallop was first to return and he put himself in the front rank of the first battalion, so that there was nobody between him and his enemy.

When Otto and his people saw that the King had returned, which they had not expected, they were surprised and overtaken by sudden fear. They then turned to the right side of the road so that they were going west and spread themselves out to the extent that they covered the greater part of the field. They came to a stop facing north so that the sun shone directly into their eyes, a sun which was hotter and brighter on this day than previously. The King called up his battalions and positioned them in the fields right in front of his enemy and facing south in such a way that the French had the sun at their shoulders. Thus were the battalions organized and evenly positioned on both sides. In the middle of this arrangement was the King in the front rank of his battalion: at his sides were William des Barres, the flower of chivalry, Bartholomew of Roye, an elder and wise man, Gauthier the Young, the chamberlain, a wise man and good knight of sound counsel, Peter Mauvoisin, Gerard La Truie, Stephen of Longchamp, William of Garlande, Henry the Count of Bar, a young man old with courage, noble in strength and virtue – he was the king’s cousin and had recently received the county after the death of his father – and many other good knights whose names are not given here, of marvelous virtue and marvelous ability in the use of arms. All these had been put in the King’s battalion specially to protect his person and because of their great loyalty and reputation for outstanding prowess. On the other side was Otto in the middle of his people; he had had raised as a standard a golden eagle above a dragon attached to the top of a tall pole.

Before the start of the battle, the King addressed his barons and his people; and even though they already had the heart and the will to do well, he gave them a short speech in the following words: “Lord barons and knights, we are putting all our faith and hope into God’s hands. Otto and his people have been excommunicated by our Father the Apostle because they are the enemies and destroyers of things holy of the Church. The deniers at their disposal and with which they are paid have been taken through the tears of the poor and by stealing from clerks and churches. But we are Christians and follow the dictates of the Holy Church, and even though we are sinners like other men, we nonetheless submit to God and the Holy Church. We guard and defend it with all our ability and this is why we must fearlessly trust in the compassion of Our Lord who will allow us to overcome our and His enemies and to win.” When the King had thus spoken, barons and knights asked for his blessing and he, with a raised hand, prayed so as to bring the benediction of Our Lord over them. They had the trumps and trumpets sound and then attacked their enemies with great and marvelous daring.

At this time and place behind the King were his chaplain who is the writer of this account and a clerk, and as soon as they heard the sound of the horns they began to chant and pray out loud the psalm Benedictus Dominus Deus meus, gui docet manus meas ad proelium, etc., the whole of it till the end, and then Exurgat Deus, the whole of it till the end, and Domine, in virtute tua laetabitur Rex, the best they could as tears and sobs hindered them greatly. ‘then with pure devotion they recalled to God the honor and freedom which the Holy Church enjoys under King Philip’s rule, and in contrast, the shame and indignities which she suffers and has suffered at the hands of Otto and King John of England. Through the gifts and promises of the latter, all these enemies had been worked up against the King in his own kingdom and some of them were fighting their liege lord whose welfare they should rather have been protecting against all men.

The first assault of the battle did not occur where the King was, as; before those in his echelon and proximity could start the fray, others were already fighting against Ferrand and his people on the right side of the field without the King being aware of it. The first line or the French battalion was positioned and organized as we have described above and extended 1,040 paces across the field. In this battalion was Brother Guerin, the Elect of Senlis, fully armed, not to do battle but to admonish and exhort the barons and other knights to fight for the honor of God, of the King, and of the kingdom, and for the defense of their own welfare. There were also Eudes, the Duke of Burgundy, Mathew of Montmorency, the Count of Beaumont, the Viscount of Melun and other noble combatants, and the Count of Saint-Pol whom some suspected of having made agreements with their enemy in the past. And because he was well aware of this suspicion, he quipped to Brother Guerin that the King was to find him to be a good traitor today. In this same battalion were 180 combatants from Champagne which the Elect Guerin had organized: he moved some of them from the front to the rear as he felt them to be cowardly and fainthearted, while those he felt to be courageous and eager to fight, in whose prowess he had faith and confidence, he put in the first echelon and told them: “Lord knights, the field is large, spread yourselves out so that the enemy does not surround you and because it is not fitting that some become the shields of others. Rather, arrange yourselves in such a way that you can all fight together at the same time, all in one front.” After he said this, he sent ahead, on the Count of Saint-Pol’s advice, 150 mounted sergeants to start the battle. He did this with the aim that the noble combatants of France, whom we have named above, would find their enemy somewhat agitated and worried.

But the Flemings and the Germans, who were very eager to fight, greatly scorned being first challenged by sergeants instead of knights. Because of this, they did not deign to move from their position but waited and received them very harshly; many of their horses were slain and they suffered many injuries but only two were wounded unto death. These sergeants were born in the Soissons valley; they were full of prowess and great courage and were fighting no less virtuously on foot than on horseback.

Gautier of Ghistelle and Buridan, who were knights of noble prowess, were exhorting the knights of their echelon to battle and were reminding them of the exploits of their friends and ancestors with, it seemed, no more fear than if they had been jousting in a tournament. After unhorsing and striking down some of the above mentioned sergeants, they left them and turned toward the middle of the field to fight the knights. They were then met by the battalion of the Champenois, and they attacked and fought each other valorously. When their lances broke, they pulled out their swords and exchanged wondrous blows. Into this fray appeared Peter of Remy and the men of his company; by force they captured and brought away this Gauthier of Ghistelle and John. Buridan. But a knight of their group called Eustache of Malenghin began to yell out loud with great arrogance “Death, death to the French!” and the French began to surround him. One stopped him and took hold of his head between his arm and his chest, and then ripped his helmet off his head, while another struck him to his heart with a knife between the chin and the ventaille and made him feel through great pain the death with which he had threatened the French through great arrogance. After this Eustache of Malenghin had thus been slain, and Gautier of Ghistelle and Buridan had been taken prisoners, the daring of the French doubled; they put aside all their fears and made use of all their strength as if they were assured of victory.

Following the mounted sergeants whom the Elect had sent ahead to start the battle, the Count Gautier of Saint-Pol moved with the knights of his echelon who were all hand-picked and of noble prowess. He threw himself unto his enemies as fiercely as a hungry eagle throws himself unto a crowd of doves. Many he hit and many were those who hit him as soon as he plunged into the fray. There, the bravery of his heart and the prowess of his body came to the fore as he struck down all those who reached him, and he killed men and horses indifferently and without taking any prisoners. Along with his people, he struck and slaughtered left and right so much that he beat a path all the way through the crowd of his enemies, then threw himself back in from another side and encircled them so that they were in the middle of the battle.

After the Count of Saint-Pol, the Count of Beaumont made his move with as great courage. Mathew of Montmorency and his people, the Duke Eudes of Burgundy who had many a good knight in his troop, all threw themselves into the press eager and burning to fight, and waged marvelous battle upon their enemies. The Duke of Burgundy, a corpulent man of phlegmatic temperament, fell on the ground as his steed was killed under him. When his people saw him fall, they gathered all around him and soon had him climb on another horse. After getting back up, he felt greatly upset by his fall and said he would avenge this shame; he brandished his lance and spurred his horse, then threw himself with great anger into the thickest of his enemies. He paid no attention to where he was striking or whom he was fighting, but avenged his misfortune equally on everyone as though each of his enemies had slain his horse.

The Viscount of Melun, who had in his troop knights of renown, practised in the use of arms, was fighting at the same time. He attacked his enemies from another side in the same manner that the Count of Saint-Pol had done; he went all the way through them and came back into this battle from another point. In this fray, Michael of Harmes was hit with a lance between the hauberk and the thigh. He was pinned to his saddlebow and horse, and both he and the horse were thrown to the ground. Hugh of Maleveine and many others were thrown as their horses were slain, but out of great virtue they jumped up and fought with no less prowess on their feet than on their horses.

The Count of Saint-Pol, who had fought very strongly and for a long time and was already quite worn out by the many blows which he had given and received, withdrew from the press in order to rest, catch his breath, and regain his composure. He had his face turned toward his enemies. As he was thus resting, he noticed that one of his knights had been so well surrounded by his enemies that he could not see an opening through which he could come to him. Even though the count had not yet caught his breath, he put on his helmet, laid his head on his horse’s neck, and hugged it firmly with both arms; then he pricked his spurs and in this manner reached his knight through all his enemies. Then he stood up on his stirrups, drew his sword, and distributed blows so great that he split and broke the press of his enemies with his marvelous virtue. After having freed his knight from their hands at great danger to himself, through great courage or folly, he returned to his battalion and his troop. As those who witnessed the following have since recounted, at this point he came into great mortal danger as he was hit by twelve lances at the same time, and yet, with the help of his outstanding virtue, no one could bring either him or his horse down. After accomplishing this marvelous feat and having recouped with his knights who had been resting during this time, he pulled himself together, wrapped himself in his armor, and threw himself back into the thickest of his enemies.

In this place and in this hour, so intense and heated had the fighting, which had already lasted three hours, been on both sides that Pallas, the goddess of battles, was fluttering above the combatants as if she did not yet know to whom she should grant victory. At the end she piled up all the weight of the battle on Ferrand and his people. Ferrand, struck to the ground, injured and hurt with many large wounds, was taken prisoner and tied up with many of his knights. He had fought so long that he was as if half-dead and could not endure fighting any more when he surrendered to Hugh of Mareuil and his brother John. As soon as Ferrand was taken, all those of his party who were fighting in this part of the field fled or were killed or captured.

While Ferrand was thus brought to defeat, the Oriflamme of Saint Denis returned, followed by the legions from the communes which had gone forward to the tents earlier, especially the communes of Corbie, Amiens, Arras, Beauvais, and Compiegne, and they rushed to the King’s battalion toward the spot where they saw the royal standard with the azure field and golden fleurs-de-lis which a knight called Galore of Montigny was carrying on that day. This Galore was a very good knight and very strong, but he was not a wealthy man. The communes passed in front of the King, opposite Otto and his battalion. But the members of his echelon who were knights of great prowess soon forced them to retreat to the King’s battalion; they gradually scattered them all and made their way through them to the point where they came very close to the King’s echelon. When William des Barres, Guy Mauvoisin, Gerard La Truie, Stephen of Longchamp, William of Garlande, John of itouvray, Henry the Count of Bar, and the other noble combatants who had been specially put in the King’s battalion to protect him saw that Otto and the Teutons of his battalion were coming straight to the King with the sole aim of seeking his person, they put themselves in front of him so as to meet and curb the Teutons’ temerity. They left behind their backs the King for whom they were concerned. While they were fighting Otto and the Germans, the Teuton foot soldiers who had gone on ahead suddenly reached the King and, with lances and iron hooks, brought him to the ground. If the outstanding virtue of the special armor with which his body was enclosed had not protected him, they would have killed him on the spot. But a few of the knights who had remained with him, along with Galore of Montigny who repeatedly twirled the standard to call for help and Peter Tristan who of his own accord got off his steed and put himself in front of the blows so as to protect the King, destroyed and killed all those sergeants on foot. The King jumped up and mounted his horse more nimbly than anyone would have thought possible. After the King had remounted and the rabble who had brought him down had all been destroyed and killed, the King’s battalion engaged Otto’s echelon. Then began the marvelous fray, the slaying and slaughtering by both sides of men and horses as they were all fighting with wondrous virtue. Killed right in front of the King was Stephen of Longchamp, valorous and loyal knight of total dedication; he was struck by a knife through the eye hole of his helmet all the way to the brain. In this battle the King’s enemies made use of a type of weapon which had never been seen before. They had long and slender knives with three sharp edges from the point to the guard, and they were using these in the battle as swords and glaives. But through the grace of God, the glaives and swords of the French along with their virtue, which never faltered, overcame the cruelty of their enemies’ new weapons. They fought so strongly and long that they forced the whole of Otto’s battalion to fall back and retreat so close to him that Peter Mauvoisin, who was more powerful at arms than wise in the ways of the world, took him by the bridle and tried to pull him out of the fray. But he saw that he could not accomplish his aim on account of the press and the great number of his people who closely surrounded him. Gerard La Truie, who was nearby, struck him in the middle of the chest with a knife which he held unsheathed in his hand, and when he saw that he could not pierce through (because of the thickness of the armor with which warriors of our time are equipped and which is impenetrable), he gave him a second blow to make up for the failure of the first. He thought that he was going to hit Otto’s body but instead he met the horse’s head which was high and raised; he dealt it a blow right in the eye and the knife, thrust with great virtue, slipped all the way to its brain. The horse, feeling this great blow, took fright and began to struggle strongly. He turned back towards the area he had come from in such a way that Otto showed his back to our knights and ran away on the spot. He left as prize for his enemies the eagle and the standard and everything he had brought to the field. When the King saw him thus leave, he told his people: “Otto is running away, from now on we will not see his face.” He had not fled very far before his horse dropped dead. Then a fresh one was brought to him and after mounting it he took flight as fast as he could, as he could withstand no more the virtue of the knights of France, seeing that William des Barres had twice grabbed him by the neck but could not get a good hold because the horse was strong and skittish and because of the press of his followers.

At the place and time that Otto fled, the battle was wondrously violent and heated on both sides. His knights were fighting so strongly that they had thrown down William des Barres and slain his horse as he had gone further forward than the others. This happened because Gauthier the Young, William of Garlande, their lances broken and their glaives bloodied, and Bartholomew of Roye, a good knight and wise man, and the others who were with them, judged and said that it was dangerous to leave the King alone behind them, following unprotected. On this account, they did not wish to go as deeply into the fray as the Barrois had done, who was on foot against his enemies and, as usual, defended himself with marvelous virtue. But because a man alone on foot cannot last very long against such a great number, he would have ended dead or captured had it not been for Thomas of Saint-Valery, a noble knight, powerful at arms, who appeared there with fifty knights and 2,000 sergeants and freed the Barrois from the hands of his enemies.

There the battle waxed again because, as Otto was fleeing, the noble knights of his battalion were fighting strongly. They were Bernard of Ostemale, who was a knight of great prowess, Count Othe of Tecklemburg, Count Conrad of Dortmund, Gerard of Randerode, and many other knights, strong and daring combatants, whom Otto had specially chosen for their great prowess to be at his side in the battle and to protect his person. All these were fighting marvelously and were destroying and killing our people. Nevertheless, the French overcame them and captured the two above mentioned counts and Bernard of Ostemale and Gerard of Ramrode. The chariot on which the standard was resting was destroyed, the dragon broken and the golden eagle, its wings torn off and in pieces, brought to the King. Thus was Otto’s battalion completely destroyed after he ran away.

Count Renaud of Boulogne who had been in the fray continually was still fighting so strongly that no one could vanquish or overcome him. He was using a new art of battle: he had set up a double row of well-armed foot sergeants pressed closely together in a circle in the manner of a wheel. There was only one entrance to the inside of this circle through which he went in when he wanted to catch his breath or was pushed too hard by his enemies. He did this several times.

Count Renaud, Count Ferrand, and the Emperor Otto had sworn before the start of the battle, as was learned later from the prisoners, that they would turn neither to right nor to left, that they would fight against no echelon but that in which the King was. And they had planned on killing the King as soon as they captured him with the intention, once the King was slain, of easily doing what they wanted with the whole kingdom. Because of this pledge, they would at no time engage anyone but the King’s battalion. Ferrand, who had taken this same oath, wanted to go directly towards the King and began to do this but he could not because the battalion of the Champenois blocked his way and fought so strongly that it thwarted his aim. Count Renaud as well, avoiding all other battalions, engaged the King’s battalion and came directly to him at the start of the fray. But then, when he came near him, he became horrified and, as some believe, was overcome by a natural fear of his rightful lord. He turned toward another part of the press and fought against Count Robert of Dreux who was in the same battalion and close to the King in a very thick crowd.

Count Perron of Auxerre, who was the King’s cousin, was fighting virtuously for the King, but his son Philip, because he was Ferrand’s wife’s cousin through his mother, was fighting against his father and the French crown. This was because sin and the Enemy had caused the hearts of some to be so blinded that, even if they had a father or brothers and cousins in the King’s party, the fear of God did not prevent them from fighting and, if they could, they would have chased away in shame and embarrassment their rightful lord and all of their blood kinsmen whom they should have naturally loved.

Count Renaud had at first opposed doing battle even though he ended up fighting more virtuously and longer than anyone else but, as one who well knew the daring and prowess of the knights of France, he had strongly advised against fighting. For this reason, Otto and his people had suspected him of treason, and had he not consented to the battle they would have made him prisoner and tied him up. He spoke to Hugh of Boves about this just a moment before the battle: “Here is the battle which you extol and advocate and which I put down and advise against; it will come of this that you will run away as a bad man and a coward and I will fight at the risk of my life knowing full well that I will either be killed or captured.” After saying this, he went to the place assigned to his battalion and fought more strongly and longer than anyone else of his party.