William of Puylaurens covered events relating to the history of Languedoc from the twelfth century to the mid-1270s. The main subject of his history is the Albigensian Crusade, which lasted from 1209 to 1229. Along with the Historia Albigensis of Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay and the Chanson de la Croisade Albigesoise, this text is one of the three main contemporary narrative sources for the Albigensian Crusade. While the other two accounts come to an end shortly after the death of Simon de Montfort in 1218, William provides details about the later years of the crusade.

William of Puylaurens covered events relating to the history of Languedoc from the twelfth century to the mid-1270s. The main subject of his history is the Albigensian Crusade, which lasted from 1209 to 1229. Along with the Historia Albigensis of Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay and the Chanson de la Croisade Albigesoise, this text is one of the three main contemporary narrative sources for the Albigensian Crusade. While the other two accounts come to an end shortly after the death of Simon de Montfort in 1218, William provides details about the later years of the crusade.

William lived from about 1200 to about 1275, and served in the households of two bishops of Toulouse, as well as Count Raymond VII. Although he supported the Crusade against the heretical movement known as Cathars, William was also critical of the crusaders at times, including even Simon de Montfort. Unlike the other two accounts, William’s is more evenhanded, and in the words of one historian, “the product an intelligent and reasonable man.”

The section below begins with the future Raymond VII, count of Toulouse, laying siege to the crusader-held fortress of Beaucaire in 1216. Events seem to turn against Simon de Montfort, leader of the crusading forces, and he begins a siege of the city of Toulouse, which lasts from October 1217 to July 1218. This siege ends with the death of Simon

Chapter 26: The son of the Count of Toulouse lays siege to Beaucaire, and is in turn besieged by the Count of Montfort

So, after his reception by the citizens of Avignon and the people of Venaissin, the son of the Count of Toulouse entered the town of Beaucaire in strength, with the support of the inhabitants, and laid siege to the crusader garrison in the castle. He invested the castle from all sides, by land and from the river Rhone, so that no one could leave and no relief could reach the garrison from outside.

Count Simon [de Montfort] rushed to besiege the besiegers, but after eating their horses and running completely out of supplies the garrison surrendered the castle to their enemies, having received guarantees that their lives would be spared. As his efforts had come to nothing Count Simon raised the siege of the town. As a consequence many who had concealed their opposition to him lifted up their horns, and numerous strongholds and towns at once joined his enemies.

For the citizens of Toulouse, whose hostages had already returned home, as I reported above, refused to submit to masters whose rule was overweening and took refuge in a form of disobedience. They bore with difficulty the yoke which undermined the liberty to which they were accustomed.

Accordingly Count Simon – fearful that if he took no steps to suppress them they would become as a swelling tumour, decided to oppose them with armed force and punish their arrogance severely.

Chapter 27: The Count of Montfort invades Toulouse, after setting fire to various parts of the city

So, in the year 1216, the Count entered the Cité with a large armed force. He started fires in several places hoping that the citizens would be put in dread by a double storm, of fire and sword, and thus be more readily thrown into confusion. The Toulousians met force with force, they placed wooden beams and wine casks in the streets and repulsed the attackers. All night long they had no rest from fighting fire or the enemy.

In the morning the venerable father Bishop Fulk took with him some of the citizens, and in the hope of adverting the impending dangers, mediated between the two parties to secure an agreed peace and sought to blunt the sharp edge of steel with silver. The Count’s resources had been exhausted by the expenditure he had incurred at Beaucaire, and he had no money. Seizing on this some of his associates, claiming that it would be of his advantage, urged him to claim compensation of thirty thousand marks, from the Cité and the Bourg – an amount they could well afford – as a means of enabling them to gain the Count’s favour. He willingly fell in with this counsel of Achitofel, and, blinded by money, did not see the dangers that might result. For those who gave this advice well knew that levying this sum would result in much wrong being done, to the community as a whole and to individuals; this would drive the Toulousains to aspire to their erstwhile freedoms and recall their former lord. When the levy came to be collected it was exacted with a harsh and cruel pressure; not only were pledges demanded, but the doorways of houses were marked with signs. There were many instances of this harsh treatment which it would take too long to describe in detail, as the people groaned under the yoke of servitude.

Meanwhile the Toulousains engaged in secret discussion with their old Count [Raymond VI], who was travelling in Spain, concerning his possible return to Toulouse, so that their wishes might be fulfilled.

Chapter XXVIII: The elder Count of Toulouse returns from Spain and regains control of the city

So in the year 1217, whilst Count Simon was engaged in a long struggle with Adhemar of Poitiers on the east side of the Rhone, the Count of Toulouse took advantage of the opportunity so created to cross the Pyrenees and enter Toulouse, not by bridge bit by the ford under the Bazacle. This was in September. He was accompanied by the Counts of Comminges and Palhars and a few knights. Few people were aware of his arrival; some were pleased, others who judged the likely future turn of events by what had happened in the past, were displeased. Some of the latter therefore retired to the Chateau Narbonnais with the French, others to the Bishop’s house or the cloister of St. Stephen or the monastery of Saint-Sernin; the Count persuaded them to return to him after a few days, by threats or flattery. The Count Guy, who was in the area, tried to suppress this latest insurrection by force but was repulsed and could not achieve his aims.

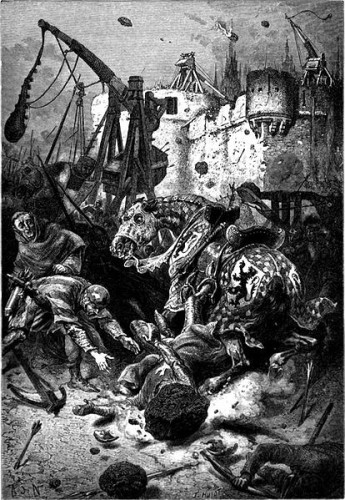

In the meantime, whilst Count Simon, currently engaged in besieging Crest, was being apprised of these events, the citizens began to cut off access from the Chateau Narbonnais to the Cite, with pales and stakes, large wooden beams and ditches, starting at the rampart known as le Touzet and going as far as the rampart of St James. Count Simon now arrived with Cardinal Bertrand, who had been sent as legate by the Supreme Pontiff Honorius, attacked the city with a strong force, but the citizens defended themselves courageously and his efforts were in vain. Then siege-engines were erected on all sides of the city, and a bombardment of mill-stones and other heavy stones was begun.

Meanwhile the legate sent Lord Fulk, the Bishop of Toulouse, to France to preach the cross; with him were others entrusted with the same mission including Master Jacques de Vitry, a man of outstanding honour, learning and eloquence, who later became Bishop of Acre and then a cardinal of the Church of Rome. The lord Bishop of Toulouse once spoke to me of Master Jacques, who had told him that he had been enjoined in a dream by a vision of St. Saturnin, the first Bishop of Toulouse, to preach against his people; he referred the matter to the Bishop and asked him if there had at one time been a priest at Toulouse called Saturnin – he had not previously known this.

The preaching mission resulted in a great many men taking up the cross; these came to take part in the siege of Toulouse in the following spring, and the Bishop returned to the army with them. Count Simon now donated to the Bishop and his successors as bishops of Toulouse in perpetuity the castrum of Verfeil, with all the towns and forts which belonged to it and which contained twenty hearths of less; the count retained nothing, and imposed only one condition that if he were ever to become involved in warfare on open ground in the territory of Verfeil, the Bishop would provide him with one armed knight.

The labour of battle oppressed the besieged and the besiegers alike throughout the winter, as they fought with siege-engines and the other instruments of war. Count Simon, now strengthened by the presence of the newly arrived crusaders, harried his enemies, less by direct attacks on the walls of the town than by excursions around it (which the citizens hindered by erecting barriers and digging ditches). At last it was decided to construct a wooden engine of the type known as a ‘cat’, which would enable his men to bring up earth and wood to fill up the ditches; once the ditches had been levelled they would be able to engage the enemy at close quarters and effect an entry into town after breaking up the wooden barriers opposing them.

However the Count [Simon] was worn out by his labours, despondent and weakened and exhausted by the drain on his resources; nor did he easily bear the prick of constant accusations be the legate that he was unthinking and remiss. Whence, it is said, he began to pray to God to give him peace by the remedy of death. One day, the day after the feast of St John the Baptist, he went into the cat, and a stone thrown from an enemy mangonel fell on his head; he died at once. The news reached the citizens inside Toulouse that day, and they did not hold back from showing their delight by shouts of rejoicing, whilst on the other side there was great sadness. Indeed the citizens were in great distress through fear of an imminent attack; moreover they had few remaining supplies and little hope of gathering their harvest that summer.

So, the man who inspired terror from the Mediterranean to the British sea fell by a blow from a single stone; at his fall those who had previously stood firm fell down. In him who was a good man, the insolence of his subordinates was thrown down. I affirm that later I heard the Count of Toulouse (the last of his line) generously praise him – even though he was his enemy – for his fidelity, his foresight, his energy and all the qualities which befit a leader.(1)

Notes

1. The poet of the Chanson de la Croisade Albigesoise took a very different view of Simon de Montfort. Referring to an epitaph which said Simon “is a saint and a martyr who shall breathe again and shall in wondrous joy inherit and flourish, that he would rise again and enter his inheritance and flourish, shall wear a crown and be seated in the kingdom of heaven.” He retorts: “And I have heard that it said that this must be so – if by killing men and shedding blood, by damning souls and causing deaths, by trusting evil counsels, by setting fires, destroying men, dishonouring paratge, seizing lands and encouraging pride, by kindling evil and quenching good, by killing women and slaughtering children, a man can in this world win Jesus Christ, certainly Count Simon wears a crown and shines in heaven above.”

This text is from The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: The Albigensian Crusade and its Aftermath, trans. W.A. Sibly and M.D. Sibly (Boydell, 2003). We thank Michael D. Sibly and The Boydell Press for their permission to republish this text.