Translated by David Crouch

Philip de Remy (d.c.1264) was a poet, novelist and knight from the region of the northern Ile-de France. He was in royal service by the 1230s, being bailiff of the Gatinais from Count Robert of Artois, brother of Louis IX of France, until the count’s death in 1250. Philip made a fortune from his job (his enemies alleged by corruption) and built a large and handsome residence on his ancestral estate near Compiegne, a house he called proudly Beaumanoir. Philip had other interests however: he was a poet and a writer of romances. In one of his most famous romances, ‘La Manekine’ (c.1241) he described the perils and adventures of a Hungarian princess called Joie (nicknamed the ‘Manekine’ or ‘Little Lass’). Joie, fleeing from her father, took refuge in the kingdom of Scotland, where the anonymous king met and married her. Following the marriage the king left for Flanders to join the tournament circuit and gain reputation. The passage below described his fortunes.

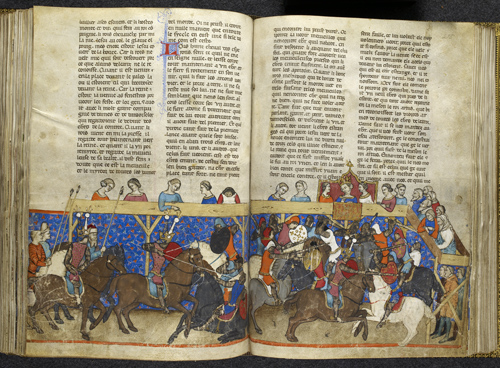

The Manekine can be dated by its resonances with the real historical marriage of King Alexander II of Scotland and Marie de Coucy (one of Philip’s neighbours) in June 1239. It is not out of the question that Philip went to Scotland to attend the marriage ceremony. The entire account of the fictional king in France is based on real-life reminiscences of the tournament circuit, not least in the location in which Philip sets it: for the tournament field between the towns of Ressons and Gournay was a genuine and long-lasting tournament venue. Not only that, but it was just across the little river Aronde from Philip’s home at Beaumanoir. What we have here is in fact a fictionalised account of a tournament created out of Philip’s own memories and experiences, and the earliest and most authentic picture of what an early tournament was actually like.

The king sailed through the night and as the morning broke he arrived directly at the Damme [the seaport of Bruges] without bad weather or any particular trouble. He arranged for his horses to be disembarked from their boats on the shore, which was accomplished smoothly. The king then entered the town, where lodgings were engaged for him. He had enquiries made about the present whereabouts of the count of Flanders, if he might be accessible. He was told that the count was at Ghent where he was making his preparations to go to a tournament at Ressons-sur-Matz; the king was delighted to hear the news. The next day, ready to move on, he took the road to Ghent at first light. The count of Flanders had heard of the king of Scotland’s arrival and hurried out to meet him, giving him greetings and a warm welcome.

The count said: ‘My lord, I am delighted that you have chosen to come here. I and my people are entirely at your disposal, whatever you have in mind to do.’

The king replied: ‘Many thanks indeed’. And so they came to Ghent, talking as they went, and spent the night with the count. The king asked him about the tournament and where it would take place. The count told him: ‘At Ressons’.

At this the king said: ‘We will go there. We would ask one thing of you, that you will be willing to join my military household for the occasion.’ The count happily consented.

The Scots spent a very comfortable night, and nothing was lacking to put them at their ease. Very early the next morning they took to the road. They came that night to Lille. They spent a good night in the town, for it belonged to the count. The next day they again set off very early. They passed to the east of Artois and then entered Vermandois, taking the route through Roye [near Montdidier] and so they came to Ressons. The king dismounted in the town, and with him the Scots and the Flemings. People had begun to arrive and to arrange and occupy their lodgings, people from Boulogne, Artois, Brabant, Vermandois, Flanders, Normandy, Ponthieu, as well as Germans, Hainaulters and Bavarians. All these folk took lodging at Ressons, and they fixed outside the windows many shields and banners of various types. On the other side [of the tournament ground] towards Gournay came people from Beauvais (I know it well), from Berry, Brittany, the Ile de France, Poitou, Anjou and Champagne also. Such people dismounted at Gournay for the tournament.

So the day came on which the tournament was to happen. When it came, they went straight to hear mass, and then they armed themselves and mounted on their destriers. They rode out on to the field to tourney: a sight to alarm the faint-hearted.

The king of Scotland rode out first in the company of 1000 knights which he had retained with him. He had equipment so very fine that there never was seen its equal. His horse, which was large and tall, was covered with figured cloth of gold, the richest that ever had been. The king, who was handsome and well-built, was in appearance beyond compare, and as well-armed as he could be. That day he carried no other device on his arms other than that they were of gold, and as well made as they were tough. He did this as a sign that he had achieved his heart’s desire. His actual coat of arms was of three rampant lioncels [little lions] in black on a golden field. Those were what he should have carried, but he had omitted the lioncels and simply carried the golden field. The count of Flanders was with him, who was to serve him well that day.

[smartads]

When both sides had ridden out from Ressons and Gournay, and had entered the field, if you had been there that day you would have seen many a fine horse, shield and banner, of all sorts of fashion. Some black, some white, some gold, some silver and others again of red; they were painted in many colours. The bright sunlight made the colours very splendid. Music was to be heard on all sides, horns and drums, and at that moment the trumpets blared out and echoed across the field. In this way the two sides came out and quickly passed in review, in which it was established with whom each knight rode and to which household he was attached. Then each man took his place and each took the shield recognised as his, and placed his helmet on his head. The king showed his household what shield of his they should recognise, and one knight acted as his attendant. Then he had his helmet laced on which was not in the least rusty, for it was made of shining and bright gold, a pleasure just to look at.

When the king had his helmet laced on his head he rode to the front of his company. He knew much of love and arms, and he gripped his shield close to his side and took his heavy lance in his hand. He urged his horse and it surged forward, and he did not cease from spurring it on till he came up to the fighting. He approached a French knight who had good reason to regret that he did not run away from the king, for he rode at him so rapidly that he knocked the knight and his horse both on to the ground. The knight could not do other than fall, for both his saddle girths gave way and tipped him on the ground. The king had broken his lance, and now he drew his sword, which he put to good use that day. The combat was soon swirling about him. Over a score of knights tried to get to him, one made a grab for his arm, another his body. But he was so powerful and active and managed his horse so well that they could not bring him down. He was able to hold his attackers off until his company rode up. They jostled and shouted to get up with the king and fought off the attacks from either side. They exchanged such strokes that it seemed that he would be deafened. More than fifteen hundred lances flew into splinters. Many were knocked down as a result and plenty of horses were grabbed and captured, and many more mounts galloped across the field, their reins trailing on the ground. Some squires ran after them to capture them, others to recover them.

Now the tournament was fully engaged, where there were so many fine companies and well-mounted knights, and the other sort also, flat on the ground. One knight wins, and another loses, for the game sorts out who has the skill and who has not. Skirmishes are going on in over a score of places, and people are tumbling to the ground, and often they take sword blows on the head, and sometimes, if they are lucky, on the shields if they have got them in the way. Each knight fights his combat and is not always happy with the blows he gets, for if he gets in one, three land on him. The king shows himself to be more than equal to anyone who has ridden to the tournament. He gives and takes many blows and strikes out to left and right. Anyone who takes him on is likely to end up flat on the ground. After that there is no point in their going to seek their horses, for they are no longer their concern. The king applied himself to the good fight, to attack and defend as well as he can, and devoted himself entirely to it. He put his whole heart into the fighting and is so wrapped up in the cut and thrust that he was the object of everyone’s attention that day. One man said to another: ‘Look at the marvels that man is accomplishing! It is hardly worth watching anyone else. He seems to be everywhere at once. Do you see how he takes and hands out blows? No one can long stand up to the sort of punishment he is handing out. He really must get recognition for such skill. He is the sort of man to lend money to, for he well knows how to reap rewards. See the shield slung at his shoulder! A dove could fly through it without touching its wings on the framework! There never was so fine a king who came from overseas to acquire a reputation and behaved so well. All knights must love him well, praise him and value him.’

All the knights in the various companies who had the space and time to do so watched the king. The rest fought and pushed, and damaged many a fine hauberk. A good few knights were sent somersaulting from their saddles that day, their helmets were crushed and faces bloodied. Some men did well out of it, others badly; some were forced to walk off the field, others rode; one lost and another won. There were many on the field who lost their horses and had afterwards to hand them over to those who had overcome them; they well regretted their losses. In many places were forges smoking to heat up the flames. For the swords there had been so hacked about that, had it been a wood, 2000 carpenters sawing could not have made such a din.

Such was the manner of that day and so it went on till night fell. But the night came and parted the combatants. Then they arranged it that there is another review, but very different from the first one: it was far more subdued. Most of the participants were worse for wear from the heavy blows they had taken. So they leave on foot or horseback and returned to their lodgings. The king came to Ressons and his friends with him, they rode right into the town. When he got there he was well enough, for he had been hit far less than he had struck out at others. He removed his armour quickly as did the count of Flanders, who had done very well that day although I did not mention it. If I had gone into what everyone had done, I could never get on with my story. So don’t ask for any other information than that he had done well. The king issued an order that all might have dinner with him who wished to do so; there was no knight left in Ressons who was not invited by him. They were supplied with plenty of food and wine. When the meal was over it was nearly morning; so they went off to their beds for the sleep that they all had need of. They slept till mid-morning. Then they rose and dressed and returned together to the king’s court. The king did not ignore them; he made much of them, showed them great affection and called them his friends and companions. He made up their losses to many of them and retained the best knights in his household, giving them many fine gifts. He could be so generous because he had the prize for the tournament; so he gave to each as befitted his merits. He spent a while making good the losses of either side; so you would find it difficult to find one national group which was willing to be less enthusiastic about him than another.

Before the king left Ressons, with the agreement of those at Gournay, he undertook to hold another tournament in a fortnight’s time at Epernay. On the king’s part he made it generally known by the announcement of a herald around the town. As they know the news is official, everyone says that he wants to go to Epernay. They began to pack their clothes and lay their hauberks within ox-hide wrappings; in this manner they readied themselves all to go to the tournament which had been announced by the king’s order. The king travelled there with his household, which was made up of fair and noble people. He loved brave knights and was very generous to them with his possessions. At Epernay, where they had gone, they tourneyed within the fortnight and the king won the prize there. In this way the king of Scotland acquired great reputation amongst the French, and worked hard to do well. It has turned out that everyone has good will towards him so far as they can; he is a man welcome everywhere he goes.

Translated from: Philip de Remy, La Manekine, ed. H. Suchier (Société des anciens textes français, 1884), lines 2615-2931, with acknowledgement to the translation by B.N. Sargent-Baur in, Le Roman de la Manekine (Amsterdam, 1999). We thank David Crouch for providing this translation.