After the Crusader’s disastrous defeat at the Battle of Hattin in 1187, the Christian forces regrouped under Guy de Lusignan, king of Jerusalem, and Conrad, marquis de Montferrat, and went back on the offensive. In 1189, the crusaders laid siege to Acre, but lacked control of the seas around the port city. Therefore, the Muslim defenders were able to continue to supply Acre. The marquis was able to gather a fleet of galleys at Tyre, and from there set off to Acre to engage the Muslim fleet. The following account of this battle, by an anonymous writer who may have been present at the siege of Acre, is heavily dependent upon Vegitius’s De Re Militari, book IV, chapters 33, 37, 44 and 45.

After the Crusader’s disastrous defeat at the Battle of Hattin in 1187, the Christian forces regrouped under Guy de Lusignan, king of Jerusalem, and Conrad, marquis de Montferrat, and went back on the offensive. In 1189, the crusaders laid siege to Acre, but lacked control of the seas around the port city. Therefore, the Muslim defenders were able to continue to supply Acre. The marquis was able to gather a fleet of galleys at Tyre, and from there set off to Acre to engage the Muslim fleet. The following account of this battle, by an anonymous writer who may have been present at the siege of Acre, is heavily dependent upon Vegitius’s De Re Militari, book IV, chapters 33, 37, 44 and 45.

Chapter 34: The battle between the enemy fleet and the fleet of our people and the marquis. Our people’s victory.

It was nearly Easter [25 March 1190], and the weather had improved. The marquis, who had fallen back on Tyre in order to repair his fleet, now returned at our people’s request with an enormous quantity of equipment and plenty of warriors, weapons and food. Our people again won control of the sea and cleared the way for ships to approach more safely. For, thanks to the princes’ mediation, the king and the marquis had been reconciled on the basis that the marquis would hold Tyre, Beirut and Sidon, and as the king’s faithful man, he would concentrate all his power on promoting the interests of the king and the kingdom. But headlong ambition always leads a greedy and wicked heart astray: burning with the desire to gain the kingdom, he broke his sworn word. He pretended outwardly to be a friend while concealing his enmity within.

The townspeople resented losing the freedom of the seas, and resolved to see what they could achieve by naval battle. So they brought out their galleys two by two and, keeping good order as they advanced, they rowed into deep water to meet the ships coming to attack them.

Meanwhile our people went on board their warships. Taking a leftwards course they withdrew to a distance, giving the enemy a clear road. The enemy ships approached. Our people prepared to engage them. Clearly there was nowhere to hide, so they determined to meet the enemy onrush head on.

Since we have mentioned naval matters, we think it appropriate to describe the battle fleet briefly and explain what kind of ships are used nowadays and what sort the ancients constructed.

Among the ancients, several banks of oars were required in ships of this kind, one above the other in steps. When they were worked, some oars had to be very long to reach the waves, and some were shorter. They often had three or four banks of oars, and sometimes five; but we read that some of the ships at the battle of Actium [31 BC] when Mark Antony fought Augustus, had six. Battleships were called `liburnas’. Liburnia is a part of Dalmatia where the fleet at the battle of Actium was mostly constructed. For this reason it became the custom among the ancients to call warships liburnas.

Yet all that ancient magnificence has faded away and vanished: for a battlefleet, which once charged the enemy with six banks of oars, now rarely exceeds two. What the ancients used to call a liburna now has a longer waist and modern people call it a galley. Long, slender and low, it has a piece of wood fixed to the prow, commonly known as a `spur’, which rams and holes the enemy’s ships.

Galliots have only one bank of oars, are short and manoeuvrable, more easily steered, run about more nimbly, and are more suited for hurling Greek fire.

[smartads]

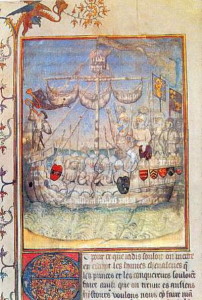

As they advanced from both sides into battle our people arranged their ships not into straight lines but curved, so that if the enemy tried to break through they could be surrounded and crushed. They formed crescents like the moon, with the stronger ships at the front, which could inflict a more violent attack while repelling the enemy’s assault. Shields were placed closely together all around the upper decks. The rowers sat in the lowest deck, to leave those on the upper deck with more space for fighting.

The sea was completely calm and quiet. It seemed to have quietened itself in preparation for the battle, so that no rolling wave would cause a shot or an oarstroke to miss. As they met, trumpets sounded from both sides, mingling terrible blasts. They opened hostilities by hurling missiles. Our people called on divine aid, worked the oars with all their strength, and drove their prows into the enemy ships. Soon battle was joined: their oars entangled and they fought hand-to-hand. They bound their vessels to each other with grappling irons, and set fire to the decks with the incendiary oil which is popularly called `Greek fire’.

Greek fire: and how it can be put out. Greek fire has a noxious stench and bluish-grey flames, which can burn up flint and iron. It cannot be extinguished with water; but it can be put out by shaking sand over it. Pouring vinegar over it brings it under control. What could be more dangerous in a conflict at sea? What could be more savage? Such various fates await the combatants! – either they are burned to death, or drown in the waves, or die from their wounds.

Our people steered one galley carelessly, exposing its nearside to the enemy. Greek fire was thrown on to it, set it alight, and Turks jumped on board from all sides. The terrified rowers immediately vanished into the sea, but a few knights who were impeded by their heavy armour and who did not know how to swim, put their trust in fighting through sheer desperation. It was an unequal fight, but in the Lord’s strength a few overcame many. They slew the enemy and triumphantly brought back the half-burnt vessel.

The enemy had invaded another ship, driven out the warriors and captured the upper deck. Yet those who were assigned to the lower deck struggled to escape with the help of their oars. A marvellous and miserable struggle ensued, with the oars pulling in different directions and the galley driven now this way by our people’s efforts and now that way by the Turks. However, our people won. The Christians attacked the Turks who were rowing on the upper deck, dislodged and defeated them.

The other side lost a galley in this naval engagement, and a galliot with its crew. Our people returned safe and sound, bearing a solemn triumph. The victors dragged the enemy galley back with them up on to dry land and left it on the shore to be plundered by our people of both sexes who came running to meet them. Our women pulled the Turks along by the hair, treated them dishonourably, humiliatingly cutting their throats; and finally beheaded them. The women’s physical weakness prolonged the pain of death, because they cut their heads off with knives instead of swords.

No naval battle like that was ever seen before. It was so destructive, completed with such danger and won at such cost.

From The Chronicle of the Third Crusade: The Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, edited and translated by Helen J. Nicholson (Ashgate, 1997). We thank Ashgate Publishing and Helen J. Nicholson for their permission to republish this section.